Blog Giving young people a voice to better understand their food environments

What do young people eat? Where do they eat? Why do they eat what they eat? The answers to these questions are shaped by their food environments: the collective economic, socio-cultural, physical, and political factors that influence food choice. Understanding how food environments are configured is helping our partners in Vietnam, Kenya, and Ethiopia identify opportunities and local solutions that can drive broader change.

In this story, discover how videos made by young people are central to a co-creation process with governments, communities, and schools to improve food environments and address challenges such as food access, intake, nutrition and health outcomes.

In Vietnam

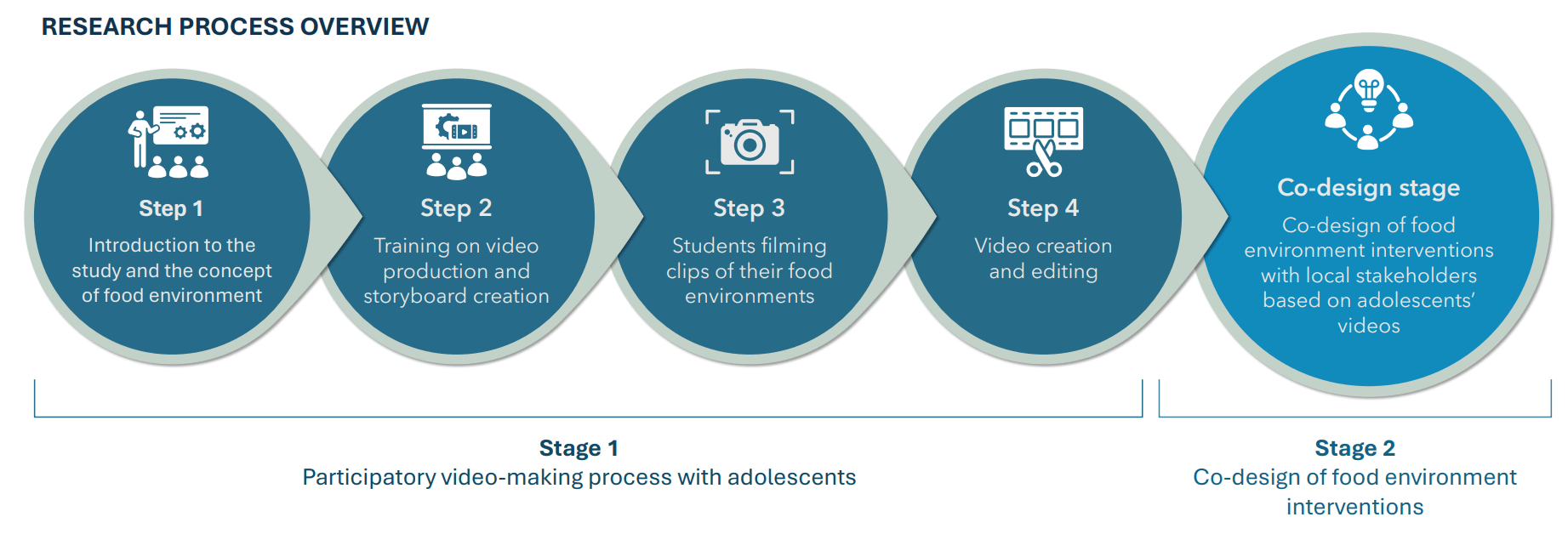

The research, developed in partnership with the National Institute of Nutrition of Vietnam, began in 2023 and was funded by the CGIAR Research Initiative on Sustainable Healthy Diets through Food Systems Transformation (SHiFT). It took place in three districts: Moc Chau (rural), Dong Anh (peri-urban), and Dong Da (urban) with 54 adolescents (aged 15–17 years) divided into six groups (3 girls’ groups, 3 boys’ groups). The first stage used participatory video-making to capture adolescents' perceptions and interactions with their food environments. The second stage expanded the process by engaging local community adults alongside adolescents (see figure 1 outlining the research process).

Figure 1. Research Process Overview

Watch the video below to learn more

The overview of the research process

The final videos produced by the adolescents were used during the co-design of community action plans to enhance food environments for better diets.

The research revealed that adolescents in Vietnam navigate highly diverse food environments, from street stalls and school canteens to convenience stores and home gardens. They have access to both fresh, locally sourced foods and a wide range of packaged, processed, and ultra-processed products. Their food choices are largely driven by affordability, convenience and taste. Key opportunities for action at the community level include increasing the availability of healthy foods in schools, replacing unhealthy food advertisements with positive nutrition messaging; and improving nutrition knowledge and skills of adolescents, households and school actors.

“Part of the vision is to make healthier food options available through increased commitment of the school and canteen to source nutritious foods and reduce unhealthy options. Increase the consumption of healthy foods by integrating nutrition education into every aspect of learning, empowering students, teachers, and staff” [Dong Anh Community Action Plan]

In Kenya

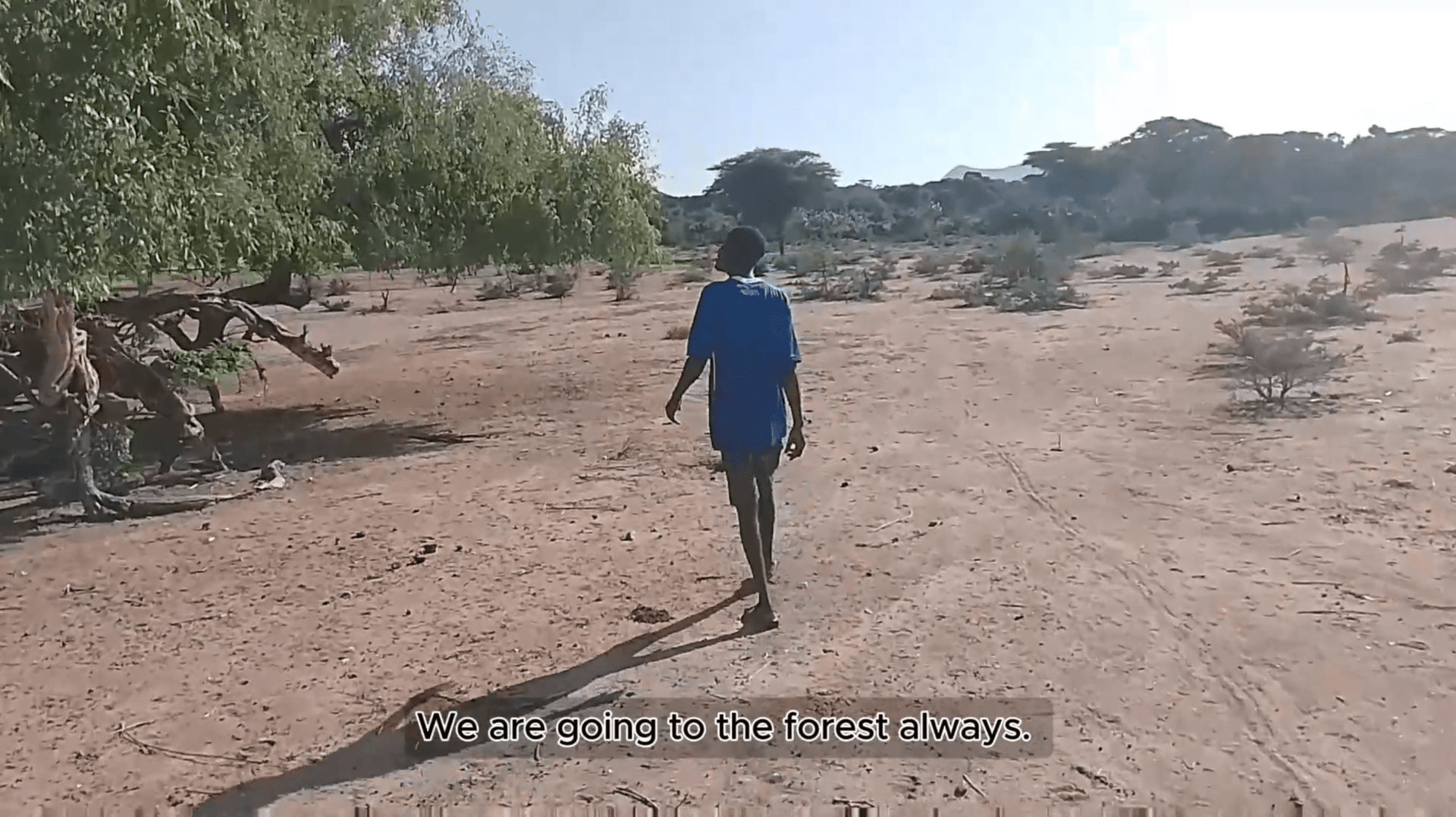

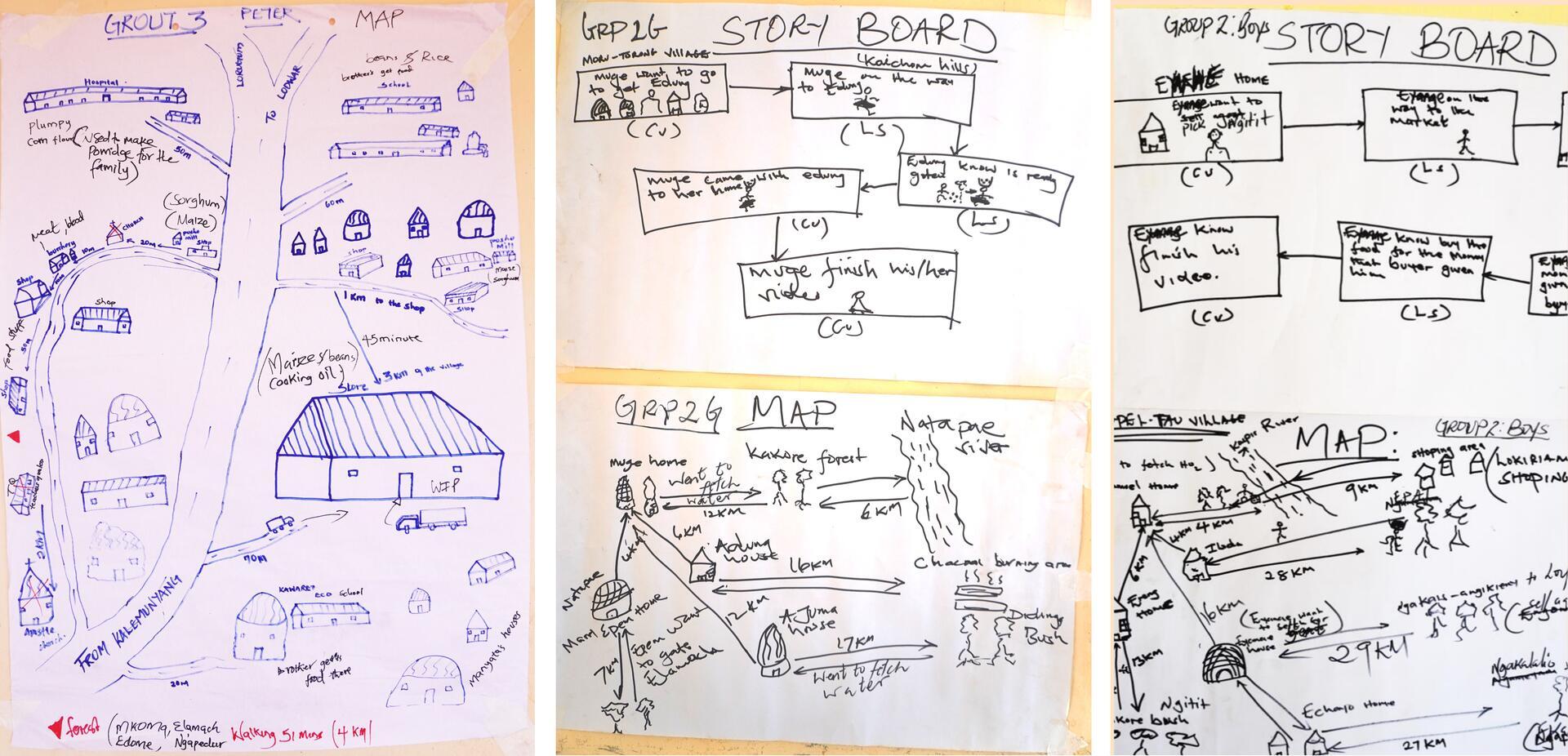

In a very different context, the participatory video experience in Kenya was developed with two communities, one agro-pastoralist and the other pastoralist. Both communities are from Turkana County, a drought-prone region with high levels of food insecurity, but with a wide range of wild edible plants that can contribute to dietary diversity and micronutrient intake when seasonal rains arrive. In 2023, 40 young adults (aged 18-24 years) formed eight groups (four groups of women, four groups of men) to capture their perceived food environment through smartphone video-making. Challenging high levels of illiteracy and low levels of digital inclusion (98% of them had never touched a smartphone before), they learned how to create maps of their food environment, create and edit videos, and develop a storyboard to guide them through the editing process. Each group produced a video.

Members of a community in Loim sub-county attend a kick-off workshop to learn how to record videos and develop storyboards.

General findings from the video process indicate that one meal per day is common, often consisting of only one item (tea with or without milk and sugar is considered a meal). Vegetables and fruits are very scarce and are mostly collected from the wild, in the forest, far away from home. Safe drinking water is rarely available, and the lack of water limits the ability to prepare food, farm, and raise livestock. Income opportunities are also very limited: trading goats or firewood seems to be the only option, but cash is needed to buy food. The titles and some screenshots of the created videos are shown below.

Life in Kotela - food environment of young women (made by girls)

New Exploring Wild Edible Plants (made by boys)

From the heart of the land - culinary heritage meets sustainable growth (made by girls)

The Pursuit of Foods - a journey through resilience, hunger and hope (made by boys)

Living off the land - Food family and field (made by girls)

Food in the face of drought - surviving the endless dry seasons in Turkana (made by boys)

Quest for sustainable food - nourishing the land - nourishing the people (made by boys)

Maps drawn by the youth. Food aid locations could be seen, and the distances are walking distances as motorized transportation in the area is very limited.

The final workshop with village leaders, extension officers, and community health workers allows participants to visualize their food environment in 5 and 10 years, identify options for change, and decide on next steps. Kitchen gardens were considered as an option to provide easy access to fresh vegetables, but are challenged by lack of water and low levels of agricultural knowledge among young adults. Restoring trees as a paid ecosystem service was also considered as a potential solution, but benefits take time to materialize.

“[We] will promote kitchen gardens in Early Childhood Development (ECD) centres to provide fruits and vegetables to learners for a balanced diet, and provide seeds and water tanks to ECD centres” Chief Education, Turkana County

The participatory video process is part of the FEnDrylands project funded by the Fiat Panis Foundation. The case study that led to this initiative was funded by BMZ with support from GIZ through the ImproDiet-Co project.

In Ethiopia

The Ethiopian experience, also funded by the CGIAR Research Initiative on Sustainable Healthy Diets through Food Systems Transformation (SHiFT), followed the same research process as Vietnam, shown in Figure 1. The journey began with community mobilization, which included explaining the study to community leaders. In the first phase of the project, 36 adolescents (aged 15-17 years) embarked on a process of learning how to make videos reflecting their food environment in two different locations: Kolfe Keraniyo (urban) and Butajira (peri-urban). The youth were divided into six groups (3 groups of girls, 3 groups of boys) in each location.

This resulted in four videos - two for each site - lasting 10-15 minutes and covering four mealtimes (breakfast, lunch, snack and dinner) on two typical days (school and non-school days). There were no significant differences between sites, although gender differences were noted in terms of engagement with the local food environment, with girls buying and preparing food more often than boys. Eating at home and sharing meals with family and friends were prominent in the videos. Watch an overview of this process below.

In the second phase of the study, co-creating community action plans, 50 participants, including youth, teachers, parents, vendors, and district health, nutrition, and education experts, were engaged to co-design interventions to improve adolescents’ access to and consumption of sustainable healthy diets.

This approach included three consecutive workshops aimed at building a common understanding of sustainable healthy diets, reviewing adolescent-produced videos, and developing community action plans. At the end of the process, stakeholders emphasized the need to improve dietary diversity: "Our meals should incorporate all food groups, however, the diet of the adolescents in the videos seemed monotonous." The stakeholders also suggested government subsidies to increase access to healthy foods and expanding school feeding programs to high schools to bridge nutritional gaps.

Data analysis is now underway and findings will be shared as soon as they are documented.

The team behind this work

Vietnam

Deborah Nabuuma

Associate Scientist

Brice Even

Research Team leader

Hang Thai

Senior Research AssociateKenya

Irmgard Jordan

Human Nutrition and Home Economic Scientist - CIM Expert

Céline Termote

Senior Scientist - Africa Regional Team leader Food Environment and Consumer BehaviorEthiopia

Mestawet Gebru

Research Officer