Blog Human behaviour, the invisible link between climate and smallholder livelihoods

A new behavior-centered guide equips practitioners to design solutions for adoption of key behaviors with the biggest implications for climate change and smallholder farmers' livelihoods.

The world is currently being fed by more than 570 million farms worldwide. Most of them are small, operating on less than two hectares, and family-run.

Just as clearing forests for cultivation and livestock grazing contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, smallholder farmers are also vulnerable to the changing climate. Increasing inputs to offset the unpredictability of seasons improves productivity in the short-term, but carries long-term costs of depleted groundwater, new pests, and reduced agrobiodiversity.

So what is preventing smallholder farmers from shifting their behaviors towards more climate-resilient practices?

The need for structural reform in the agricultural sector is immense, from improving credit access to the enduring questions of tenurial reform and land rights. But agricultural challenges are also behavioral challenges. Why are smallholder farmers reluctant to experiment with new techniques and inputs? Why is investing in soil regeneration or water conservation postponed in favor of immediate livelihood concerns?

A collaboration between the CGIAR research program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), The Alliance of Bioversity and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) , and Rare’s Center for Behavior & the Environment (BE.Center), the ‘Behavior Change for Agriculture’ Guide identifies four farmer behaviors, which if adopted, carry tremendous potential for climate and livelihoods impact.

The Behavior Change for Agriculture Guide is a collaboration between Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), The Alliance of Bioversity and the International Center for Tropical (CIAT) , and Rare’s Center for Behavior & the Environment (BE.Center).

The Guide taps into farmers’ motivations and barriers, identifies behavioral insights behind common trends in smallholder behavior, and evaluates the real world impact of four behaviorally informed solutions implemented by community-led organizations in Colombia, China, Peru, and Mexico.

Guide co-author Deissy Martínez-Barón, social scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, said, “Action at scale is required to address current challenges of climate change and it is only possible if agrifood system actors lead significant behavioral changes that empower research for development towards a sustainable transformation of the agricultural sector.”

“We wanted to show what a behavioral lens could bring to the agriculture space, and ‘solve’ an ongoing agroecological challenge with the tools of behavior-centered design,” added co-author Dr. Madhuri Karak, cultural anthropologist and consultant at the BE.Center.

Blending insights from behavioral science with design thinking, this BC4AG guide-workbook-toolkit tackles four behavioral challenges with the biggest implications for climate change as well as smallholder farmers’ livelihoods: saving native seeds; restoring and managing soils; conserving and managing water; and recording, monitoring, and cultivating smartly.

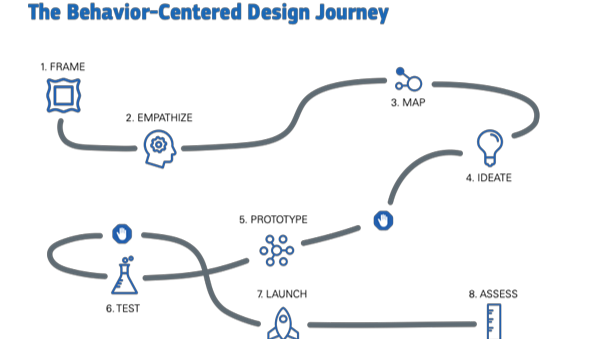

Behavior-Centered Design (BCD) is an approach that blends insights, methods, and tools from behavioral science and design thinking to build solutions for breakthrough solutions to environmental challenges. The Agriculture Guide takes users on a step-by-step BCD journey to develop behaviorally informed solutions for saving native seeds; soil management, water conservation; and climate-smart agriculture.

Paula Caballero, Regional Managing Director for Latin America at The Nature Conservancy [who was also actively involved in the elaboration of the guide], said, “This guide is an excellent resource for practitioners looking to integrate behavior change into their agriculture and climate programs. Behavior-centered design is a critical element when addressing these environmental challenges we face today.”

The Guide begins by inviting the reader to identify the actors and institutions who play key roles in each challenge. The ‘Frame’ Step, first in a 8-step Behavior-Centered Design approach, focuses our attention on the behaviors and audiences that will have the most meaningful impact on our goal.

For example, we know that non-native seeds are not only more input-intensive, they also quicken soil degradation and compromise smallholder farmers’ adaptive capacity to respond to climate variation, and the specific behavior(s) contributing to this issue is neglect of native seeds and ad hoc seed selection/storage.

After ‘Frame’, we ‘Empathize’ with smallholder farmers by learning what motivates them and the barriers they face in adopting new methods of cultivation.

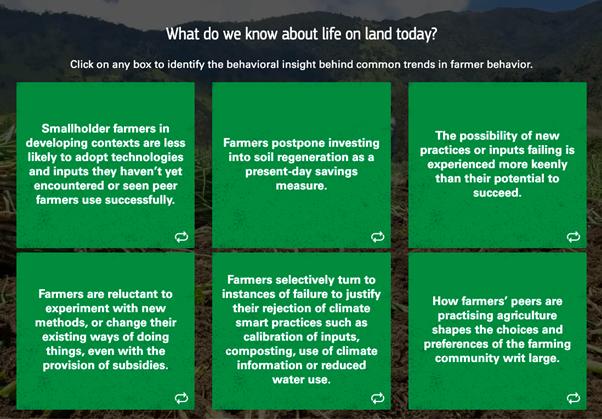

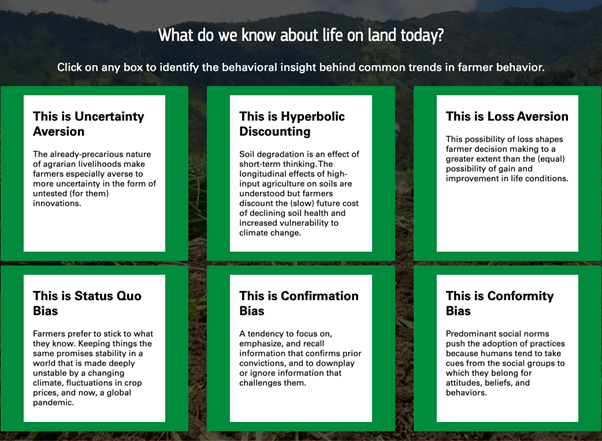

The Guide introduces users to common trends in farmer behavior during the ‘Empathize’ Step of Behavior-Centered Design.

An interactive layout takes users from problems to insights with one click. Agricultural challenges are also behavioral challenges. Understanding life on land today requires us to understand the farmers’ motivations and barriers.

With this data in hand, the ‘Map’ Step builds hypotheses. What needs to change for smallholders to start saving native seeds? This is where the six behavioral levers come in, where each lever is a category of intervention strategies based on evidence-based principles from behavioral and social sciences.

The Guide’s fourth Step ‘Ideate’ is a brainstorming session, and we get closer to real world examples of how frontline communities chose to address the challenge of promoting the adoption of native seeds.

Over ‘Prototype’ and ‘Test’ Steps, we learn the importance of developing and testing a small-scale version of an intervention. Soon enough, it’s time to ‘Launch’ our solution and ‘Assess’ its impact over time. We share the latest data from our case studies measuring the rate of behavior adoption for all four agricultural challenges discussed.

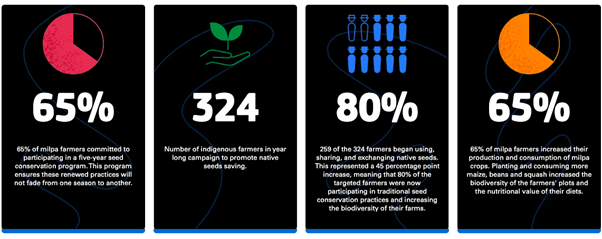

The Behavior Change for Agriculture Guide features case studies from four countries with data measuring the rate of behavior adoption in each case. The above example highlights Rare’s partnership with the Centro de Investigación y Servicios Profesionales A.C. (CISERP) in Chiapas, Mexico, promoting the use and saving of native seeds.

Figures from CISERP after a year-long behavior change campaign shows a high number of indigenous farmers choosing to use and save native seeds. The ‘Assess’ Step of the Guide encourages users to measure the impact of solutions and monitor changes in the rate of behavior adoption over time.

Through a series of interactive worksheets, illustrations, and stories from the field, this Guide centers smallholder farmer behaviors as a critical piece of the puzzle that is agriculture’s impact on climate alongside the vulnerabilities experienced by farmers in an increasingly climate-variable world.

Available in English, Spanish and Portuguese.