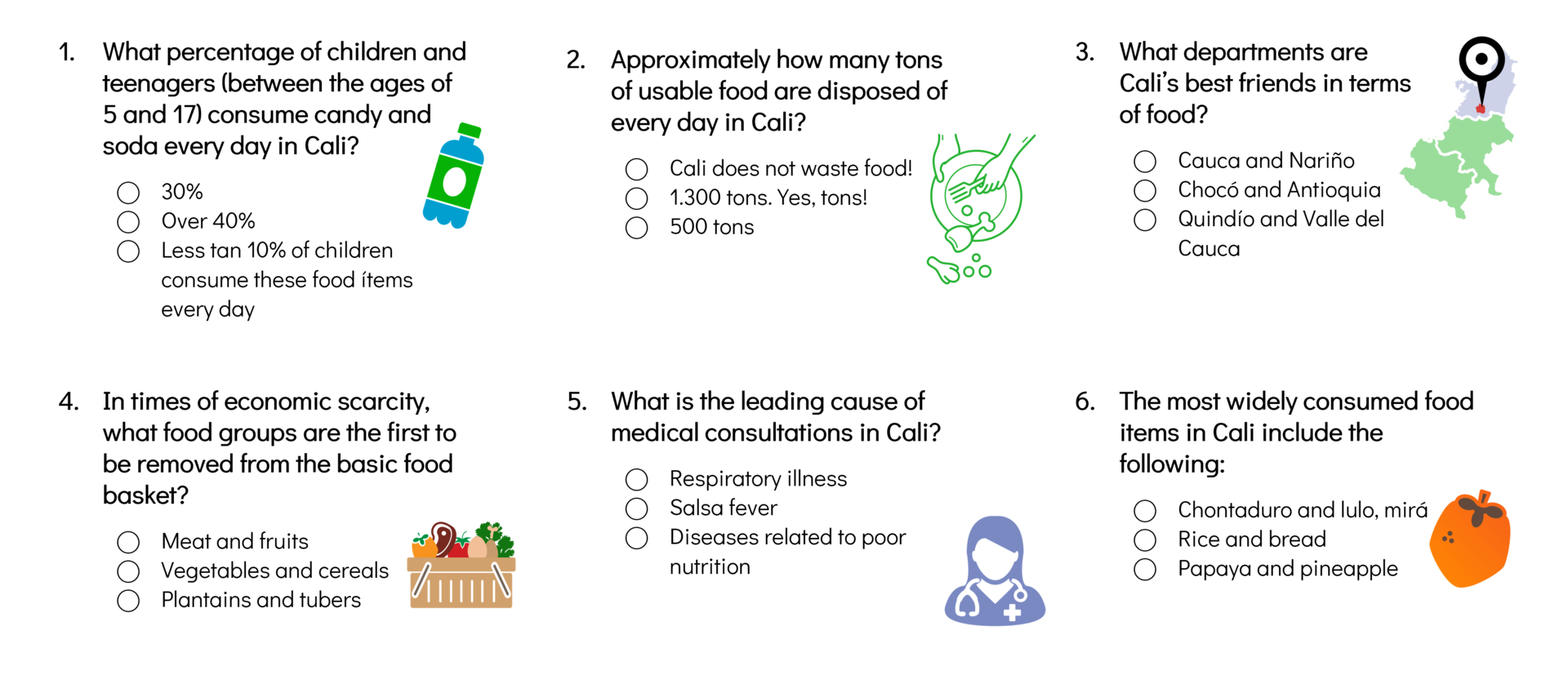

How well do you know Cali’s food system?

I was born in Cali – I won’t say how many years ago – and I assure you, if I had not taken part in the development of the City’s Food System Profile, I would have failed the following test... Would you like to try and see how you do?

Did you fail as well? Here are the answers:

1. Over 40% of children and teenagers (between the ages of 5 and 17) consume candy and soda every day. Yes, every single day!

2. 1800 tons of solid waste are disposed of every day. Yes, every single day! Out of which, 1300 tons are usable food.

3. 65% of the food products we consume are sourced from two neighboring departments: Cauca and Nariño. Nariño sources mainly tubers and plantains, vegetables, and dairy products.

4. When incomes are reduced, the first food items to be removed from the basic food basket by the inhabitants of Cali are mainly animal protein and fruits, which affects directly the nutrients and vitamins the family receives.

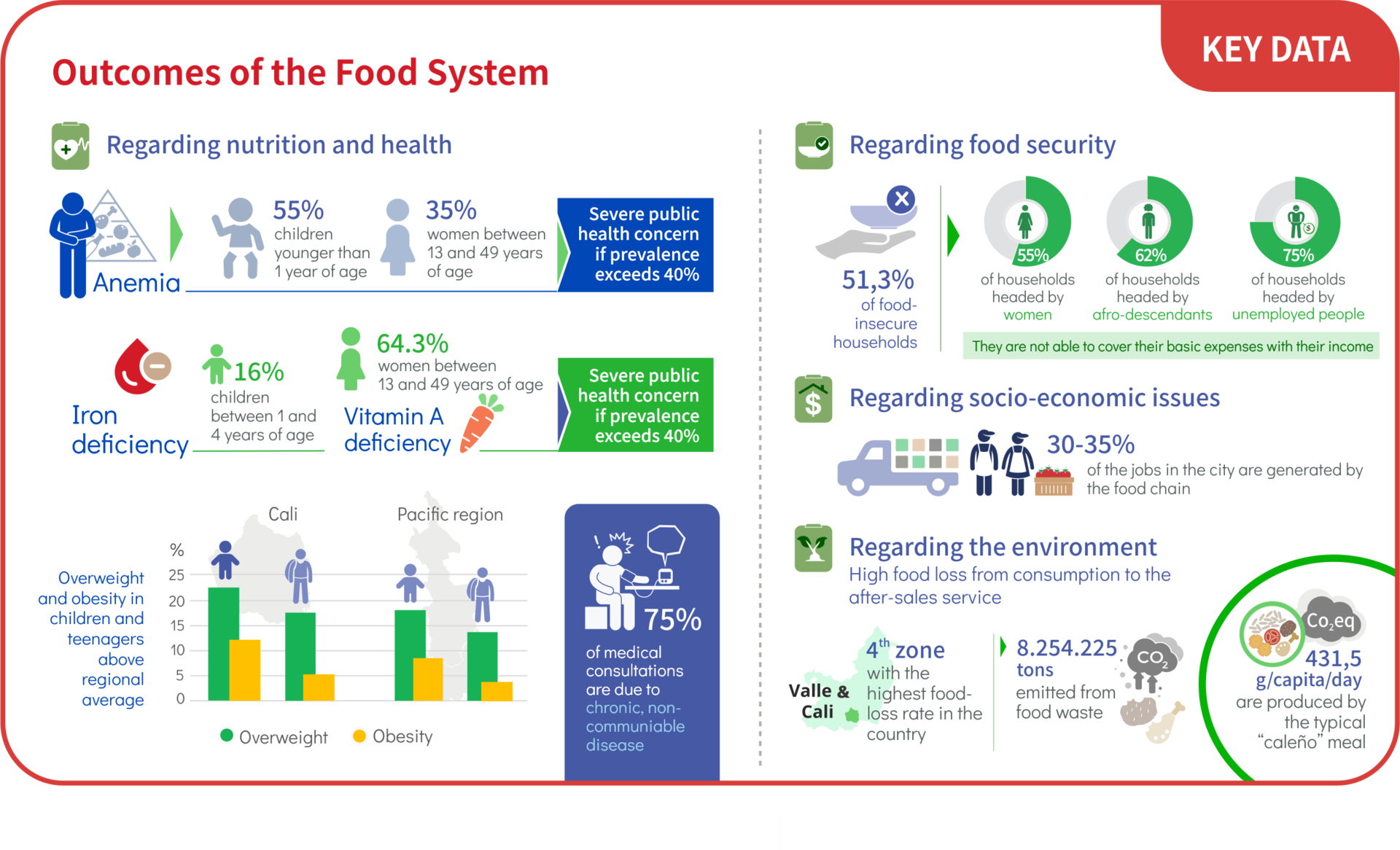

5. 75% of medical consultations in the city are due to chronic, non-communicable disease, such as high blood pressure and diabetes, which are directly related to bad dietary habits.

6. The majority of the food items most widely consumed by the inhabitants of Cali have low nutritional value, such as rice, coffee, and bread.

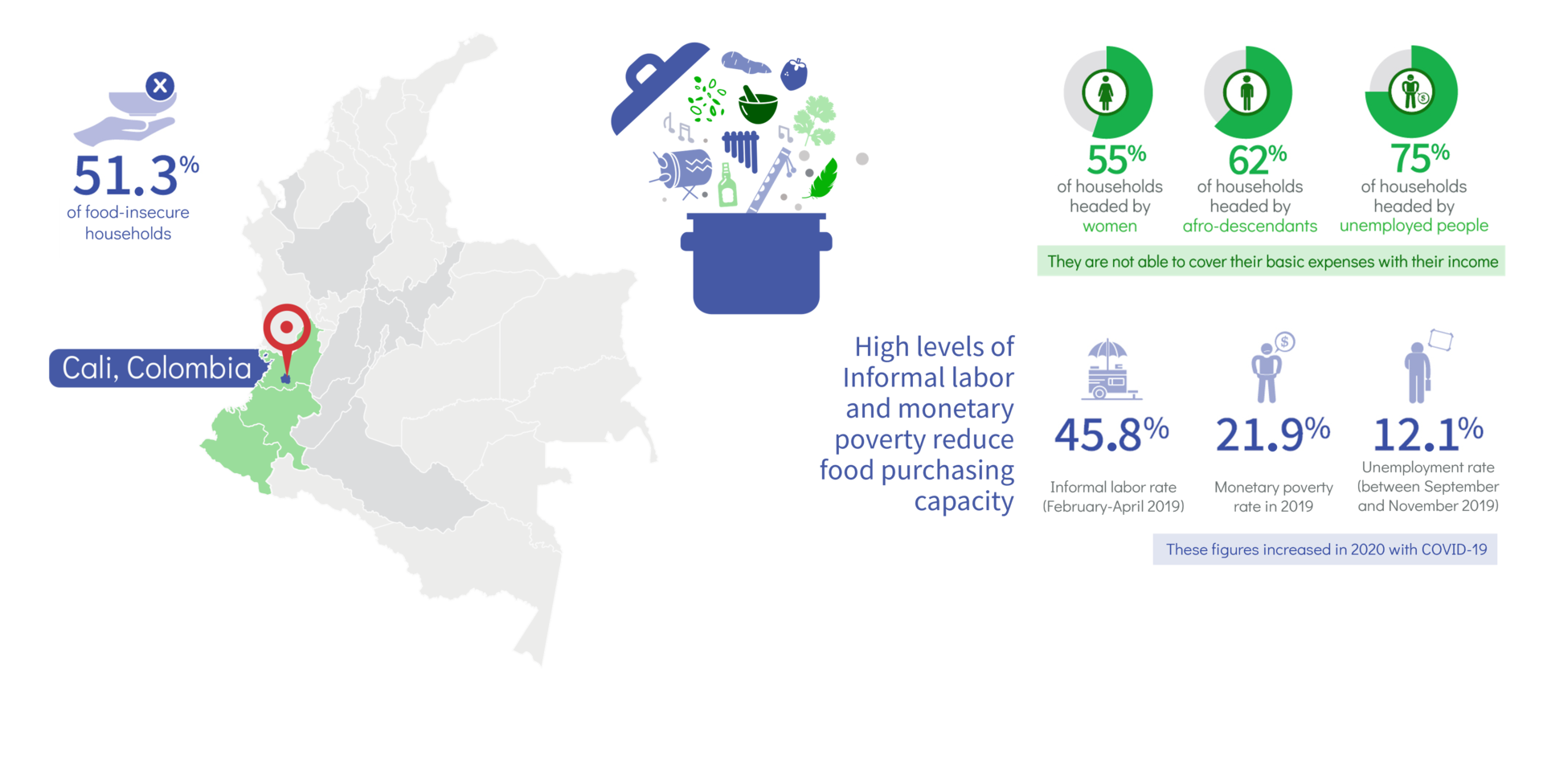

When COVID-19 knocked at our doors in 2020, the reality of a food system with numerous issues also burst into our city as well, and this profile shows us why: the number of households headed by women (55%) and by unemployed people (75%), who are not able to cover their basic expenses with their income; the number of households (51.3%) without access to adequate and sufficient food; the number of children (65.7%) between 6 months and 2 years of age, who did not receive a minimum acceptable diet; or the amount of waste we are generating each day (1800 tons) are just some of the data showing that our city’s food system was dealing with several issues even before the pandemic.

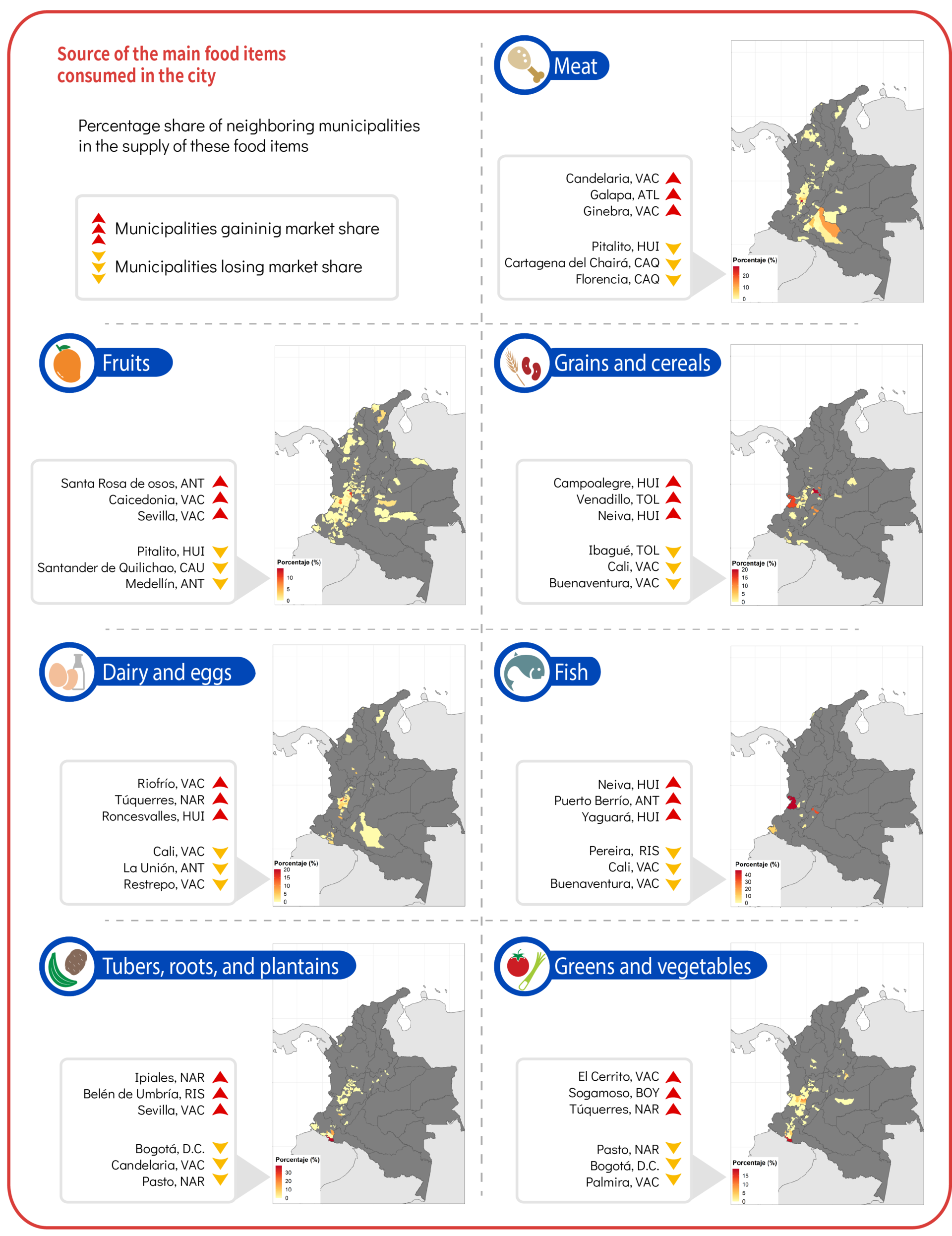

Then, in 2021, the national strike in Colombia showed how reliant is our city on supplies from other municipalities and neighboring regions. Figure 1 illustrates this well: Cali cannot be analyzed solitarily as an island, because it is part of a wide system of regional dynamics.

Figure 1. Source of the main food items consumed in the city and participation of neighboring municipalities in the supply of such items. Source: Rankin S; Hurtado LJ; Bonilla-Findji O; Mosquera EE; Lundy M. 2021. Perfil del Sistema Alimentario de Cali, ciudad-región. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia. 27 pp. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/114362

Thus, in the last 18 months, the city has faced two major resilience tests: the pandemic, which revealed a problem regarding the demand of food – people did not have money to purchase – and the national strike, which revealed a problem regarding supply – we depend on the supply of food into the city to be subsequently distributed.

What can we do with what we know... that is the question

However, what is really important here is not how much we know, but what do we do with what we know. As a team, we are very happy to be able to provide the city with this profile, but we are very aware that the complexities and challenges facing Cali’s food system will not be solved in one event; they will require turning knowledge into action – and a shared action that is. This may sound trite, but it is true. In the words of Carlos Alomía, Manager of CAVASA – the main marketplace in the city – one of the major challenges we face is community building around dietary issues.

In 2020, we joined FOLU Colombia, the Municipal Secretariat for the Economic Development of Cali, Biotec Corporation, the Pontifical Xavierian University in Cali, the World Food Program, WWF, RAP Pacífico, Arrocera La Esmeralda, El Hatico Natural Reserve, and the Government of Valle del Cauca in the Food and Land Use Alliance, which promotes an inclusive, resilient, and sustainable city-region food system to provide food for every member of society. This partnership is an all-engaging initiative and will pick up on the food system profile we are presenting today to validate, enhance, and consolidate the existing information through consultative processes with key stakeholders. This will result in a roadmap with recommendations and priority actions to guide and articulate initiatives in a 10 year horizon. This roadmap is expected to identify and prioritize actions to be scaled up, which may be implemented or strengthened through public-private coalitions.

Figure 2. Key data on the results of the food system. Source: Ibid. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/114362

A food system is a complex matter in itself; it involves many stakeholders and is so large, there are no magical formulas or standard recipes to fix it or improve it. Every stakeholder is able to see only one fragment of the full picture from the position he holds in the food system; and from there, what he sees as a solution may represent major issues for others. Indeed, the system is demanding substantial changes in the dietary habits of thousands of people in the city, but this directly conflicts not only with cultural traditions, but also with the reality that people do not have money to buy fruits and vegetables or do not have time to prepare them, because they have to work to support their family, when they have a job. Therefore, it is not always a matter of preference, it is not always a matter of indifference; it is not always a matter of ignorance, nor is it always lack of political will nor something to be blamed on the industry. Sometimes it may be, and some others it can be a little bit of everything, but concerted solutions may be generated, conducting discussions to make clear what are the possible impacts these solutions will have on the different stakeholders in the system: who will win and who will lose; making sure, of course, that the ones who lose are not the most vulnerable actors. For this purpose, during the discussion, we need to leave out the lens we are used to look through, so we can see what we have not been able to see before.

This is an open invitation and those interested may contact us to find out how to take part.

For further information, please visit:

- Understanding Cali's food system today to plan for the future

- A city region as a food lab for a greater understanding of food systems

- What happens in the city when we understand that the rural-urban link is increasingly strong? Cali’s example

- POLÍTICA PÚBLICA DE SEGURIDAD Y SOBERANÍA ALIMENTARIA Y NUTRICIONAL DE CALI: Un esfuerzo faro

Contact: Sara Rankin Cortázar, Research Associate at the Food Environment and Consumer Behavior Area of the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, [email protected]