Blog Colombia may broker historic agreement to share genetic diversity’s digital wealth

One of the world’s most biologically diverse countries could help guide world leaders toward a functional agreement on sharing benefits from digital genetic sequence information at the UN Biodiversity Conference in October. From farmers’ fields to biotech labs, the world is watching the oft-contentious debate on how to share the world’s wealth of this information transparently and equitably.

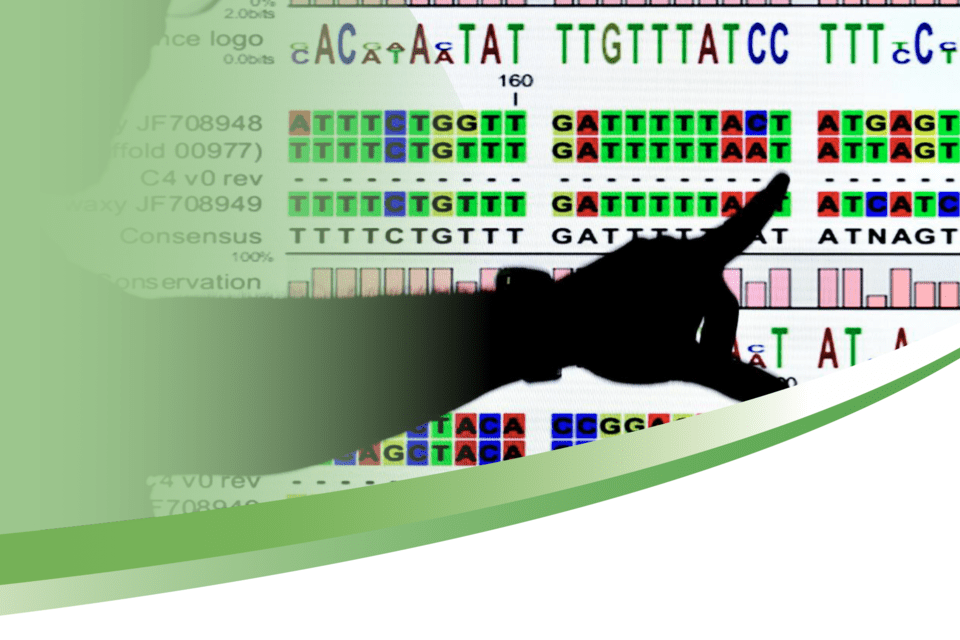

When you mention “digital sequence information” or its initials (DSI) to someone, chances are they’ll have no idea what you’re talking about. In short, DSI is a placeholder term in policy circles for the blueprints of life – DNA and other genetic information – stored in databases. Thanks to rapid technological advances, generating DSI is inexpensive, and accessing it is easy and usually free (at least from publicly managed databases), revolutionizing how we make everything from vaccines and new crop varieties to cosmetics and environmentally friendlier laundry detergents. But as of today, benefit sharing from the use of DSI is not subject to any international regulations.

The “s” in DSI, unfortunately, does not stand for “simple.” Getting the world to agree to rules for accessing and sharing DSI– which also encompasses RNA, proteins, other genetic information, and even traditional knowledge— is a complex exercise. This fall, Colombia will be hosting the 16th meeting of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), or COP16, guiding the final chapter of deal-making that aims to conclude the process.

In some ways, DSI negotiations mirror the late-to-the-party debates on regulating artificial intelligence: Technology is moving much faster than policymakers, the issues are poorly understood by non-specialists, and competing interests and poor cooperation confound the process.

And DSI is only part of the global biodiversity conservation effort: even the best-case decision on benefit sharing will not provide the resources necessary to reverse the trend of biodiversity loss. Many other forms of financial and policy support and reformed practices in a wide range of sectors will be necessary to achieve that noble goal.

“The challenge when it comes to striking a deal on DSI benefit sharing is that there’s no policy ‘stick’ that can be used to get everyone to the table. And we are pretty short on carrots as well.," said Michael Halewood, an access and benefit-sharing policy specialist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT who has been involved with UN policy processes on genetic resources since 2001. “Except of course the survival of the planet, but that has the problem of requiring long-term commitments and behavior change, and there are so many short term pay-offs for continuing our environment-destroying practices.”

Michael Halewood

Genetic Resources and Seed Systems Policies Team LeaderWho is at the table and what do they want?

Let’s introduce the DSI protagonists at the COP16 table, and what they could gain or lose by an international agreement to regulate access to digital DNA and share the benefits.

Scientists in the public sector, including CGIAR, want streamlined, open access to DSI. They’re happy to share what they do with it for free, like developing new crops to help the world’s nutrition and hunger crises. They don’t want new rules that hinder their work.

Private sector scientists want the same unhindered access. The key difference is that companies are beholden to shareholders and chief executives, live and die by patents and profits, and are therefore inclined to secrecy and unenthused by proposals that would essentially tax DSI-derived earnings. And they generally don’t want to be required to share data that they have been generating and using as part of their own product development chains.

That said, industry groups have stated that if new DSI benefit-sharing rules are inevitable, they should be administered in a way that spreads payment obligations widely and that rules be universally applicable, creating a ‘level playing field.'

Custodians of biodiversity, often marginalized Indigenous groups and other remote communities, want increased recognition and support for their conservation efforts and a more influential voice in biodiversity conservation and research discussions. They are arguably the least influential voice, but the CBD has made effective provisions to involve them in discussions.

Governments are stuck in the middle trying to keep everyone happy, but at the same time, they are reluctant to take on new responsibilities or financial burdens. Many negotiators are attracted to the notion that benefit-sharing payments should come directly from commercial users, leaving governments conveniently out of the equation.

Poorer countries– home to most of the world’s genetic diversity– want an increased share of monetary benefits from others’ commercial use of DSI, which, in theory, they would invest in protecting biodiversity. Many developing countries, however, are reluctant to give up the possibility of creating domestic regulations for access to DSI. Richer countries are hesitant to agree to substantial new payments, either directly from their budgets, or from commercial DSI users within their borders.

Meanwhile, the world is already billions of dollars short on money for biodiversity conservation. The CBD estimates that revenue from industries that use DSI will be about $1.56 billion USD in 2024, rising to about $2.3 billion by 2030. Filling part of the gap from these sources – without stifling innovation – is a sensible part of the solution.

Native quinoa varieties conserved at a communal seed bank, the Yell Ya (yell, "semilla"; ya, "casa"). Jardín Botánico Las Delicias, San Fernando, Municipality of Silvia, Cauca. Photo by Alex Reep, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

The custodians’ dilemmas

But before we get into more acronyms and jargon, scientific debates, and the DSI policy kerfuffles, what do Indigenous Peoples and local communities (for short: IPLCs) say about DSI? As custodians of rare, unique and endangered bits of DNA – like the stuff found in remote farms of ancestral crops not overtaken by industrial agriculture – their views could keep COP16 negotiators focused on conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

One reason some IPLCs feel distanced is the notion that DSI is too complicated for non-experts to understand or care about. The discriminatory vestiges of colonialism certainly play a role too.

Alexandra Reep, a visiting researcher at the Alliance, recently crisscrossed Colombia asking for opinions about DSI from people living in biodiversity hotspots. Over dozens of visits to communities spanning biomes from lowland tropical forests to the highlands, Reep found that locals recognized the stakes of the DSI rulemaking.

This is because IPLCs have weathered generations of biopiracy, the unauthorized collection of Indigenous or local flora and fauna, with nothing given in return, a practice that continues today. (In one Afro-Colombian community Reep visited, locals hide their sacred medicinal plants to avoid outright theft by “eco-tourists,” some of whom have been nabbed with backpacks filled with live turtles and cuttings of endemic plants.) To many, unauthorized digitalization of their biodiversity is just a continuation of an age-old practice.

“From the perspective of a scientist, I understand the desire for open-access information available online,” said Lorena Matabanchoy, 29, an agro-industrial engineer and community organizer for her Quillacinga Indigenous group in Colombia’s western department of Nariño. “From the perspective of a community member, I think DSI should be restricted. Community members should know what DSI from their plants will be used for and to what end.”

Matabanchoy and others told Reep they would happily facilitate access to local biodiversity for research. In turn, they want to collaborate with traditional knowledge and receive recognition, respect and support for their biodiversity custodianship. One community, in particular, would invite researchers to learn more about the properties of their medicinal plants that they claim are effective palliatives for respiratory infections, including COVID-19.

Biodiversity in Tolima, Colombia: red banana varietals. Photo by Alex Reep, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

Filling an “empty shell”

At the last UN Biodiversity Conference, COP15 in Montréal in 2022, negotiators agreed to set up rules by COP16 for access and benefit-sharing (ABS) for DSI. Initially, there was little progress. Part of the reason is that access and benefit-sharing have long been lumped together.

“Coupling of access and benefit-sharing is one of the main reasons why ABS approaches are largely ineffective,” Halewood and colleagues wrote in a 2023 Policy Forum article in Science. The publication has been a useful reference for negotiators in recent months as they try to put a palatable agreement on the table in October. In it, they said the COP15 decision on DSI was an “empty shell with no agreement on how benefits will be shared, by whom, for what and under what conditions.”

The emergence of DSI required policymakers to rethink approach access and benefit-sharing. The multilateral system the CBD is now negotiating could and should effectively separate access to DSI from sharing its benefits, requiring payments from anyone in sectors that rely on DSI (without needing to track and trace uses of DSI in particular products). This would make the system easier to implement, generate more money than other options, and guarantee continued open access. While this would eliminate the complicated task of tracing DSI to its origin, it would provide funds to support IPLCs and conservation. Communities like Matabanchoy’s could recur to national governments for benefit-sharing funds generated under the agreement.

“It is possible to have a new de-linked multilateral mechanism for DSI in public databases," Halewood said. “At the same time, the system can and should be flexible enough to address, at least partially, if not wholly, the concerns expressed by IPLCs going forward.”

Halewood explains that such a win-win scenario will depend upon mutually supportive implementation of the new multilateral DSI benefit-sharing mechanism (under the Kunming Montreal Biodiversity Framework) along with the CBD’s Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing. Under the Nagoya Protocol, contracting parties can implement national measures to provide IPLCs control over who accesses their genetic materials and how those resources are used, including whether they are used to generate DSI and how it is shared. If all contracting parties had such measures in place, going forward, DSI derived from genetic resources accessed from IPLCs would only be uploaded and available on public open access databases with IPLCs’ consent pursuant to national measures implementing the Nagoya Protocol.

The idea of benefit-sharing from the use of physical genetic resources has existed since the 1992 Rio Conventions, which formally recognized the sovereign right of nations over their genetic resources. Several agreements followed, but “despite efforts to implement these agreements, they have not resulted in satisfactory monetary benefit-sharing to support biodiversity conservation or other priorities,” Halewood and colleagues wrote.

The emergence of DSI required policymakers to rethink approach access and benefit-sharing. Separating access to DSI from the sharing of its benefits by users is the most likely avenue to successfully address the interests of everyone involved, getting benefits generated from commercialization of a much wider range of products, without the complexities of regulating access or tracking and tracing users, and heading-off the widespread problem of avoidance. Such an approach could generate considerably more monetary benefits than ‘linked’ approaches, and the money raised could be made available on a priority basis for IPLCs.

Learning from 3 decades of flaws

In the year and a half since COP 15, Halewood and colleagues have insisted that filling the empty shell must draw on lessons learned from 30 years of “fundamentally flawed” ABS systems that focus on systems where “users” (researchers or companies) make payments to countries after entering into highly bureaucratic agreements tracking and tracing the use of accessed materials into specific commercialized products.

Avoiding benefit-sharing has historically been easy because there are many unregulated sources of genetic materials. Many nations don’t have measures to regulate access to genetic resources, despite having joined the CBD and or Nagoya Protocol. Other countries decided that they don’t want to regulate access at all.

Of course, the biggest challenge as far as benefit-sharing from the use of DSI is concerned is that the CBD, Nagoya Protocol and Plant Treaty regulate access to material genetic resources but not to DSI derived from those resources. And DSI allows researchers to profit from research leads provided by DSI without accessing the material genetic resources from which that DSI was derived, effectively creating a regulatory vacuum.

Some countries have recently developed national laws to regulate access to DSI because there is currently no international agreement. Others are working on such laws. “But countries ‘going it alone’ in this manner will convolute research and development still more, subjecting different subsets of DSI to different rules,” Halewood said. "From the perspective of agricultural research and development, the more inclusive, the more harmonized, the flatter and simpler, the better.

"The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Plant Treaty) provides an interesting source of inspiration and learning, because it creates a multilateral system of access and benefit-sharing for plant genetic resources used for food and agriculture. There are 150 countries that have agreed to share plant genetic resources with one another under fixed ABS terms which are set out in the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA) that accompanies all transfers of materials under the multilateral system. The Plant Treaty also governs the 11 genebanks hosting international collections of over 750,000 different crop and forages from around the world. The centers' genebanks distribute approximately 120,000 samples yearly (the figure was close to 200,000 in 2023) to recipients around the world under the SMTA.

Learn more about CGIAR Genebanks in this video.

“It would not take much to revise the Plant Treaty’s multilateral system to include and integrate benefit sharing from the use of DSI. Negotiators under the CBD need to remember that agriculture already has a multilateral system for plant genetic resources, and that DSI benefit sharing could be integrated into that system relatively easily,” Halewood said. Indeed, there is a Working Group under the Plant Treaty that is considering options for such integrations.

In the last year, the pace of international discussions and negotiations have showed positive advances. The 100-member Informal Advisory Group on DSI has met seven times to review the list of priority issues identified by COP 15. Last month, the Co-Chairs of the Working Group on DSI released a document with their on best options for ways developing the mulilateral mechanism. Interestingly, they appear to favour an approach whereby: “An obligation to share benefits from the use of DSI is triggered when a business operates in a sector the turnover of which is substantially reliant on the use of DSI. While this trigger is linked to the use of DSI, it is unlinked from specific uses of DSI in specific products, and thus avoids the challenge associated with [an approach] requiring the identification and listing of products that “use” DSI.”

"The Co-Chairs text is very encouraging," Halewood said. "We very much hope the ‘delinked’ approach they set out will be accepted and built upon by negotiators during the second meeting of the Ad Hoc Open Ended Working Group on DSI in Montreal in August 2024."

Credits: Writing and editing by Sean Mattson; Photography and field reporting by Alexandra Reep, Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. Additional editing by Eliot Gee. A special thanks to Michael Halewood, Claudio Chiarolla and Isabel Lopez for their valuable input. Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

Cover photo: Native maize capillo is mixed with la alegria, panela, and white corn powder in an armadillo shell to be planted with marigold flowers and two varieties of beans in the Yatul (spiral-shaped plot). Jardín Botánico Las Delicias, Silvia, Cauca. Photo by Alex Reep, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

Learn more about DSI and COP16