Research Articles Striking up a new tune, gender researchers re-examine their focus on men

In a discussion with Carol J. Pierce Colfer, a CIFOR researcher with almost 50 years working on gender issues, researchers examine the growing role of “masculinities” in their research.

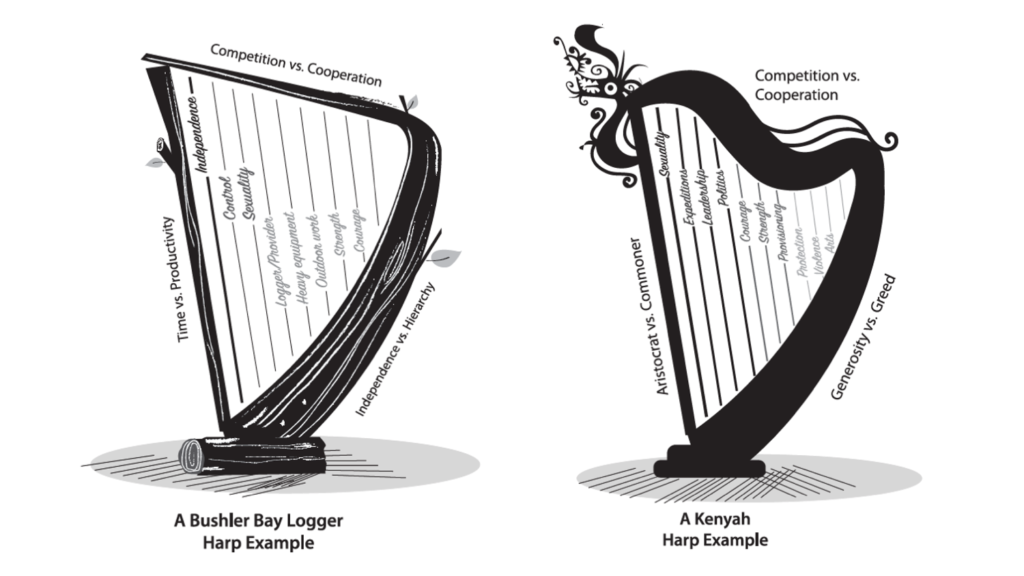

The loggers of Bushler Bay in the U.S. Pacific Northwest and the forest-dwelling Kenyah peoples of Borneo do not immediately appear to have much in common. But this very fact is a central point of Colfer’s findings: that men vary greatly from one culture to another and over time. This masculinity might not bring to mind a harp. But for Colfer, an ethnographer who worked with both communities over her 50-year career, the stringed instrument is a good analogy for the “masculinities” of these and other disparate groups of men.

“I was thinking about the shape of the harp; the rigid triangle that it creates,” said Colfer, during a recent webinar to discuss masculinities and her new book on the theme.

The strings, she explained, were the different options men had – strength, courage, control, sexuality, among others – within their particular culture.

“I was hoping to capture both the stability of culture and the individual variation in the options that men have and which change over time,” said Colfer, a senior associate researcher at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). “The fact that each man can actually, in a way, produce his own song of masculinity. Those were the kinds of thinking I had in my mind when I built on this analogy.”

An illustration of a harp fashioned from tree branches, flanked by silhouettes of loggers under tropical forests on one side and temperate forests on the other, graces the cover of “Masculinities in Forests: Representations of Diversity,” Colfer’s new book.

Colfer was joined by an international group of gender experts to discuss the oft-overlooked role of men in studies focused on women. The discussion was convened by the CGIAR GENDER Platform, as part of its series of virtual gender conversations.

Colfer’s personal and professional journeys as a researcher frame her book. In the introduction, she writes,

“In my professional life, I paid a lot of attention to women. But a few years back, I began to feel a sense of malaise. We said we were looking at gender, whereas in reality mostly we were looking at women’s worlds.”

Other gender researchers can relate. Even relatively recent programmatic changes by aid agencies underscore the need to incorporate men into work that aims to give women greater economic, professional and reproductive independence.

“While IFAD, of course, acknowledges inequalities are largely experienced by women and girls, and that selective interventions are needed to level the playing field, we also clearly recognize that the discourse around gender inequality should not only be about closing gaps with regard to women,” said Petra Järvinen, who works in the Gender and Social Inclusion team at the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).

During the discussion, Järvinen pointed to the use of household methodologies (HHM) that IFAD has been implementing in its operations since 2009. HHM’s are innovative approaches that can be applied to better understand patterns of gender inequality, particularly among farming families and communities. They tackle underlying social norms, attitudes and behaviors and involve entire households, including men and boys, and take into consideration their possible disempowerment as a negative tradeoff.

Constructive masculinities

In more than 30 years as an agronomist, Cécile Ndjebet has dedicated much of her career to securing land rights and security for women. In Cameroon, one country targeted by the African Women’s Network for Community Management of Forests (REFACOF), founded by Ndjebet, success often involves understanding the role of men in forest management.

Ndjebet said the man is generally

“perceived as the provider of the wellbeing for his family, also the owner of the resources.” Failure to meet this socially constructed role can lead to mockery by family and society – but the flip side of cementing his role is that he can become “the chief of everything,” she said.

Her organization’s advances in gender equality in forest use and conservation have stemmed from working with boys from an early age on gender sensitivity.

“Constructive masculinities go along with gender equality, respect to women’s and men’s rights and their contribution to the sustainable management of forests in general, of sustainable development,” Ndjebet said during the discussion.

Photos: Patrick Shepherd/CIFOR

Correcting inequalities, altering course

As a man who has long been doing CGIAR gender research because he is “determined to correct inequalities driven by my own gender,” Gordon Prain said his recent work has focused more on understanding that women’s empowerment does not happen in a vacuum.

“However important empowerment is, it doesn’t happen in isolation,” said Prain, an independent researcher who formally worked at the International Potato Center (CIP) and with the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas.

“Women’s empowerment, it happens through changing gender dynamics… and this requires increased research with men.”

His experience has shown that for gender norms to change, men need to be part of the equation. If not, working to reduce inequalities can be more difficult.

“Not involving men can have very negative practical implications,” he said. “Decision-making and policymaking should not buy into gender stereotypes: men can be involved in housework and child-rearing.”

The CGIAR GENDER Platform, led by Nicoline de Haan, expects to see more research on masculinities incorporated into their plans.

“It’s an area that we need to do more work on and have a better understanding,” de Haan said, highlighting various platform priorities from value chains to governance and gender-transformative research approaches. “Masculinities is something we would like to support much more.”

Here is a recording of the webinar: