Blog Decoding the food and culture connection to promote healthier foodways in Kenya

Part 3 of a series by: Irene Induli, Yasu Morimoto, Patrick Maundu and Erika Eliana Mosquera Echeverry

Food and culture are inherently connected. What natural sources people use to obtain their food, what they consider consumable and what they do not, how they prepare it, and how they consume it (in whose company and following what rites) has been determined by the beliefs of communities and their conceptions of the holy and the profane, as well as of the surrounding landscape and available resources.

All this shapes local foodways. Just imagine how many different foodways you could find in a country with more than 850 species of indigenous plants, eaten by around 60 different ethnolinguistic groups, each with their own culture. This copious diversity is key for nutrition. Our scientists have been documenting these foodways to comprehend and promote them among the young people of their communities, whom modernity is distancing from the knowledge of their ancestors.

Foodways' meaning and importance

In social science, foodways are the cultural, social, and economic practices and knowledge shared relating to the production (growing or gathering and harvesting), storage, preparation, and consumption of food, within a cultural or community setting. These foodways constitute, therefore, the socio-cultural capital of the local food systems.

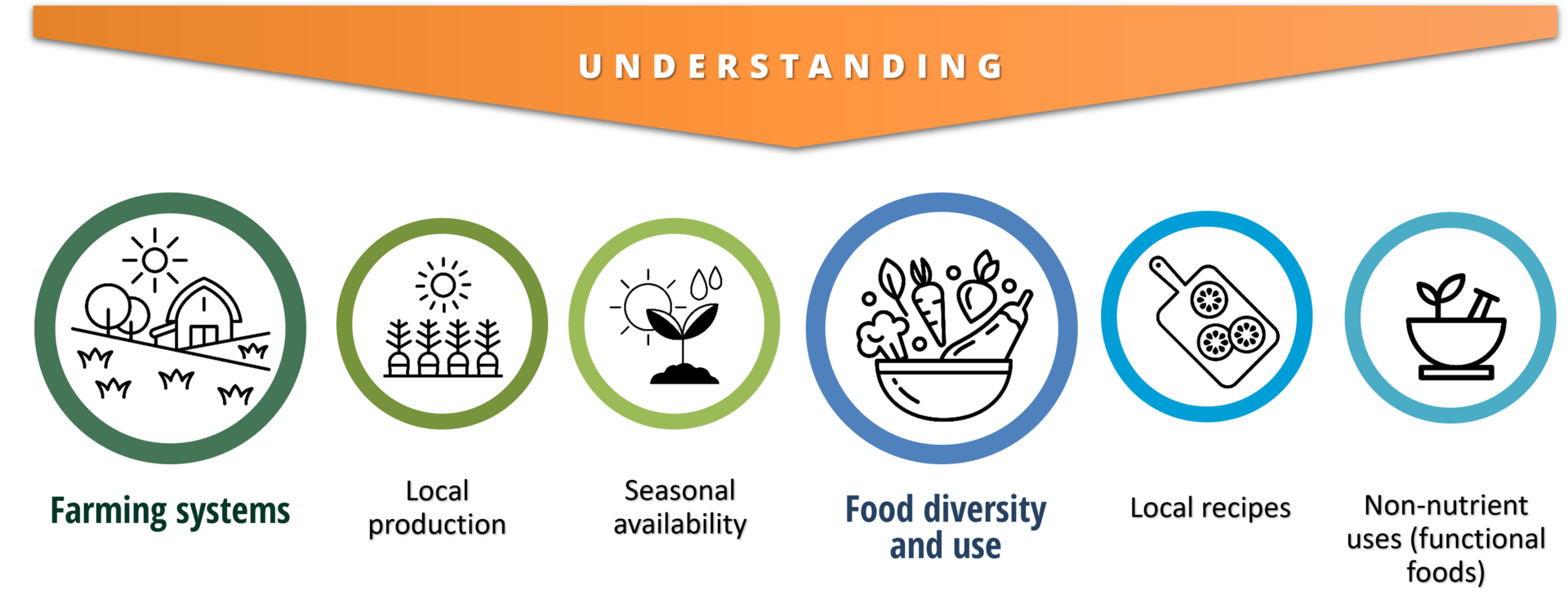

Figure 1. Potential of foodways approaches

Many African nations, including Kenya, are party to the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Identifying and documenting traditional food customs and encourage communities to practice it are key to preserve this living heritage. Thus, after Kenya's 2007 ratification of this Convention, between 2010 and 2013, Kenya Society of Ethnoecology, Bioversity International and Government of Kenya; with support from UNESCO’s Japanese-Funds-in-Trust for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage, successfully facilitated documentation of Foodways of Isukha and Pokot communities in Kenya- both of which are captured in two books. Likewise, a recent publication from our scientists digs a little deeper about Safeguarding the biodiversity associated with local foodways in traditionally managed socio-ecological production landscapes in Kenya. According to this publication:

“All cases have shown that converting underutilised local foods into main sources of nutrition and income opportunities, as well as conserving these foods in their environment, requires foodways documentation, community participation, and multi-stakeholder and multidisciplinary collaboration […]” Maundu, P.; Morimoto, Y. (2022)

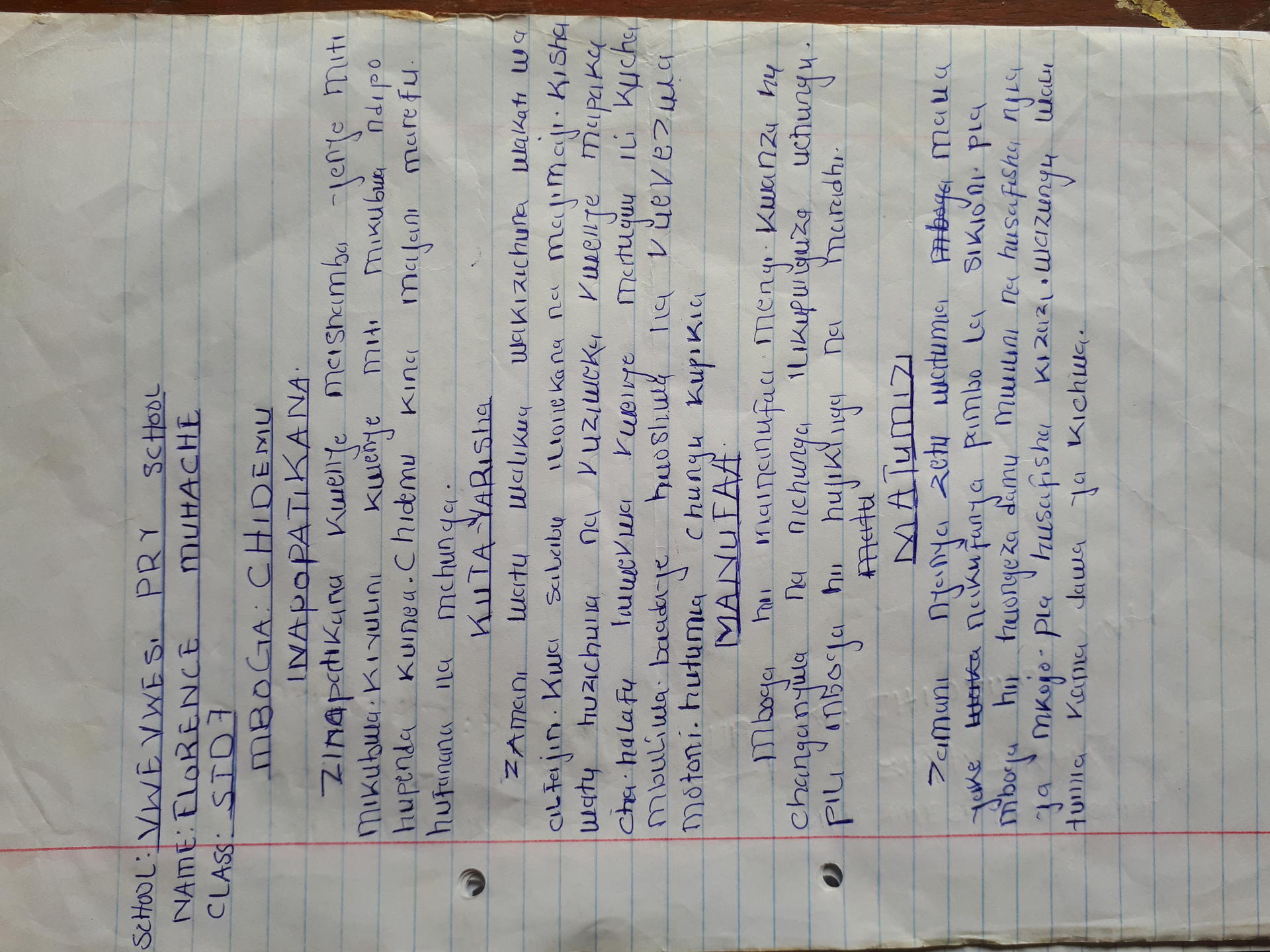

An example of a pupil story, Vwevwesi Primary School. By Patrick Maundu, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

Documenting traditional foodways in Kenya

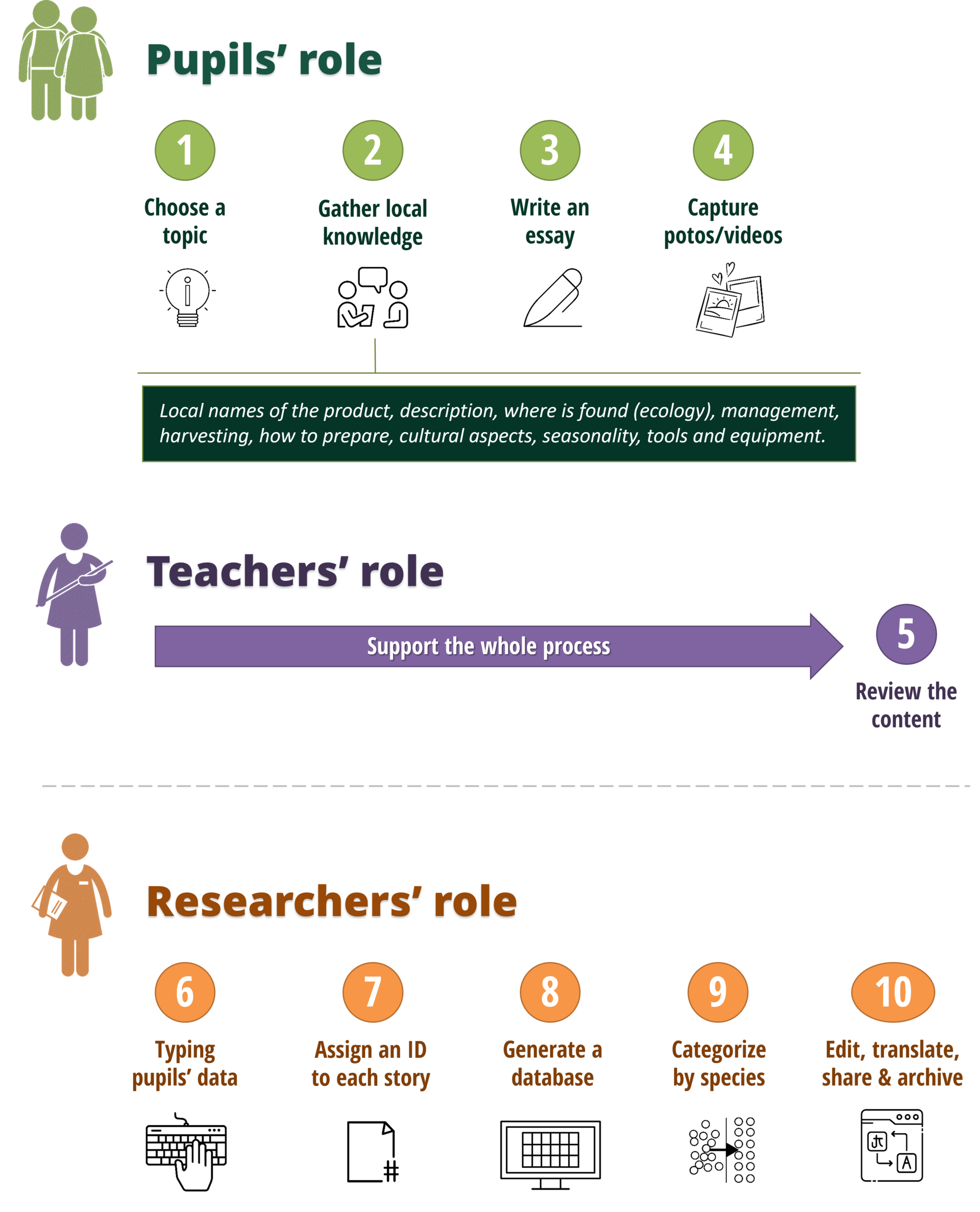

The data collection method designed by our scientists to document foodways actively involves young people, particularly school children. Pupils documented their foodways with help from their teachers, parents, guardians, and other close relatives with knowledge on those traditional foodways. Their participation was both a fun and learning activity through storytelling, photography, and field excursions. In addition, other volunteer agents from the community are also selected.

“Selected community members are trained on foodways documentation. The basic materials needed for documentation include a notebook, a simple camera with video facility, or a smartphone and storage facility like a computer. A community coordinator or champion monitors the documentation process, gathers the collected information, and keeps it at a community resource centre or an institution within the community”. Maundu, P.; Morimoto, Y. (2022)

Jaribuni Primary School participating pupils. By Patrick Maundu, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

Figure 2. Documentation at schools

However, documentation at schools is not the only way that has been taken. During all these years—almost 20—foodways documentation has been tested in 6 communities in 4 African countries: Kenya (Mijikenda, Pokot, Isukha, and Loita Maasai), Ethiopia (Gumuz), Burkina Faso (Dagara), and Tanzania (Maasai). These other experiences include, for example, the case of the Kyanika Adult Women's Group in Kitui, Kenya, who documented their foodways around Kitete (bottle gourd, whose scientific name is Lagenaria siceraria). Kitete is an ancient crop with many landraces and forms, which is not only food but also a resource for income generation since it is converted by these women into pots and cooking utensils and are also decorated and sold as ornamental items.

Kitete use in Kitui, Kenya. By Yasuyuki Morimoto, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

How foodways documentation drives healthier diets: an example

Documentation processes captured knowledge specifically around three different topics: the source of food (agrobiodiversity, ecosystem, market, harvesting knowledge); preparation (grilling, boiling, steaming, cutting, washing, flavoring, threshing and milling, mixing and shaping), and consumption (by gender, by age, on the floor, at a table). But are all those details necessary? What are the impacts of collecting and sharing this knowledge for communities? Let's take the Mijikenda example to see this in context.

Between 2016 and 2018, with funding from the European Union, our scientists carried out foodways documentation among the Mijikenda communities of coastal Kenya. A major finding was the important role played by Kayas, which residents consider sacred shrines. These sacred forests serve as a refuge for diverse foods, including crop wild relatives (wild plant species genetically related to cultivated crops). And due to the cool and wet forest cover, these Kayas are the only places where some traditional foods can grow.

The documentation of foodways around the Kayas allowed our scientists to understand the important value that these forests have for the community, not only in cultural terms but also in terms of food security and biodiversity protection. This reflects the great contribution that the documentation of foodways can make to food systems by showing the different dimensions (social, cultural, nutritional, ecosystemic) involved in the same challenge, which would facilitate the collaboration of different stakeholders around a common good.

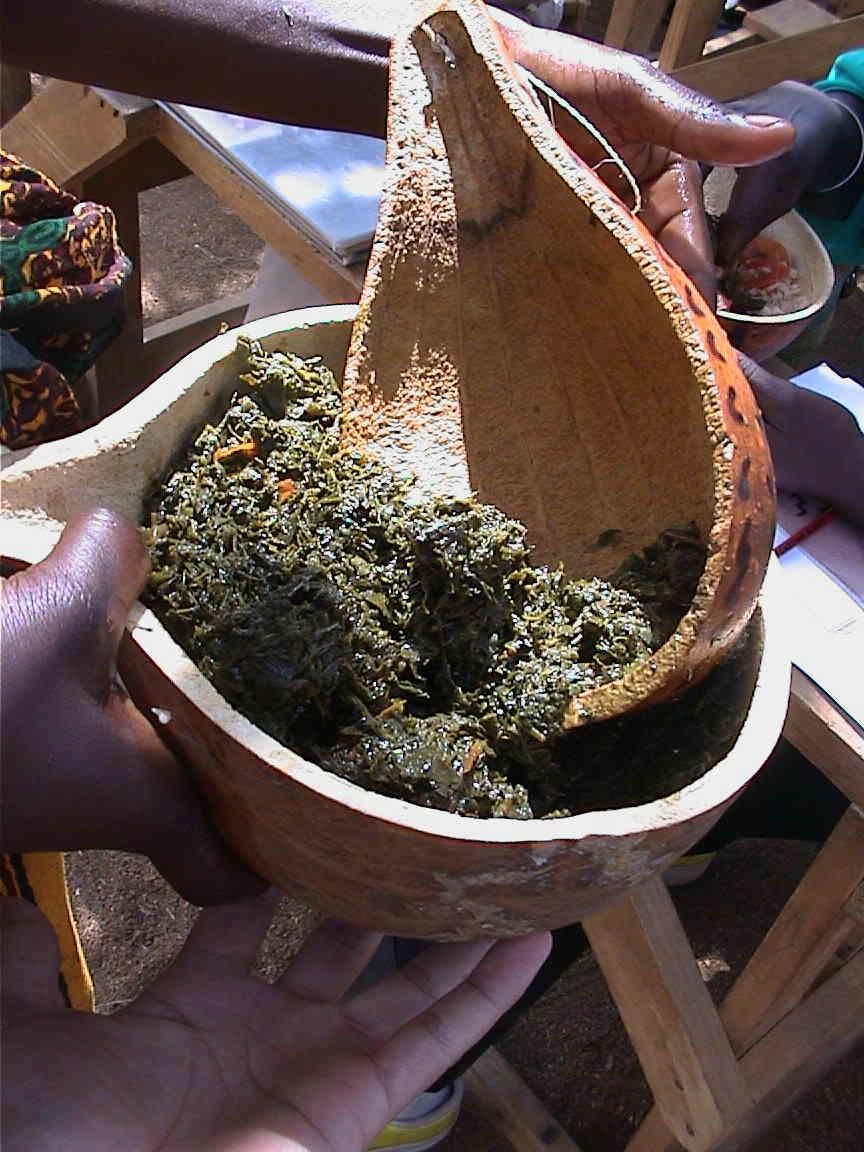

Food with African leafy vegetables using Kitete. By Yasuyuki Morimoto, Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

In addition, the documentation of foodways favors the exploration of biodiversity, which is the basis of a huge range of resources for human and ecosystem health. If we only take the example of leafy vegetables foodways documentation, just a 1.8% of the 220 species recorded in Kenya are (only) cultivated, while 7.8% are cultivated and wild, and the vast majority of species, 90.9%, are acquiring from the wild landscape. The discovery of these new species, along with the uses and preparations given to them by the community, is a prerequisite for educating new consumers, now captivated by modernity and its unhealthy eating habits. That is why the Agrobiodiversity Diet Diagnosis Interventions Toolkit (ADD-IT) is also incorporating this knowledge obtained from foodways documentation to use digital technology in the education of new generations.