New digital map of Barotse speaks both the language of scientists and farmers

In light of the 8th Ecosystem Services Partnership conference, Bioversity International researcher Natalia Estrada-Carmona reveals a new digital map of Zambia's unique Barotse floodplain which will not only allow researchers to assess the capacity of the landscape to provide nutritious food but also analyze the trade-offs and synergies between livelihoods, nutrition and ecosystem services.

As the 8th edition of the Ecosystem Services Partnership (ESP8) conference commences in Stellenbosch, South Africa, we stopped to chat with Montpellier-based Bioversity International researcher Natalia Estrada-Carmona about her work with communities in the Barotse to map their ecosystem services. She and her colleagues are launching the Barotse land type characterization map at ESP8's 'Ignite ecosystem services and poverty alleviation' session.

Bioversity International (BI):One of the recent outputs of the 'Nutrition-sensitive landscape' project is a gorgeous online map of the Barotse landscape. Can you tell us a little bit about what makes this new map special?

Natalia Estrada-Carmona: Yes, I'm thrilled to share the results of our Barotse research at ESP8 because it is such a vivid example of how important ecosystem services are for human survival. Particularly in this case, we’re thrilled that we have been able to really integrate local knowledge into the development of the map linking ecological processes with agricultural and conservation opportunities. Here at ESP8, we’ll be highlighting the trade-offs and synergies between sustainable food production and other critical ecosystem services for people living in the ever-changing and very dynamic Barotse floodplain in Zambia.

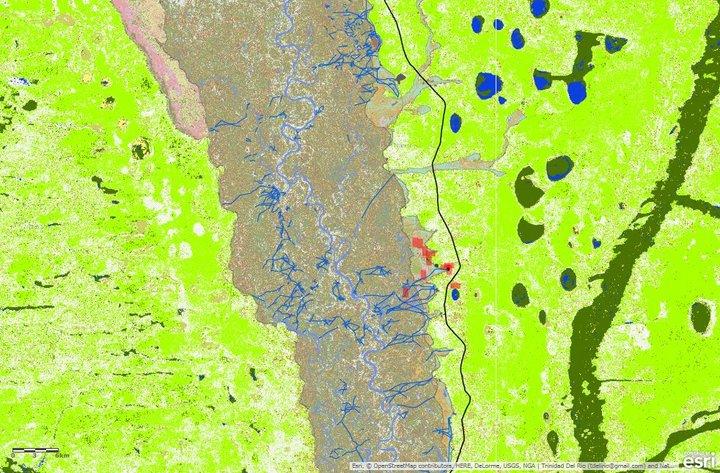

What do I mean by dynamic? In Barotse, the vegetation, cropping systems, soil quality and water availability is regulated by the intensity and duration of the annual flood pulses. The new map that my colleagues and I have just launched in collaboration with CGIAR's programs on Aquatic Agricultural Systems and Water Land & Ecosystems, tells us a story of the deep interdependence of food security of the Barotse people with this ecosystem process.

It integrates local and scientific knowledge and facilitates an exploration of the 'win-win' situations for a sustained and diversified provision of food production, nutrition and habitat for wildlife among others.

Local communities have provided names for 'land types' in the floodplain according to how they behave in the case of a flood, determine the opportunities for agriculture and for ecosystem services. Despite the importance of different land units in local decision-making and peoples' well-being, there was no integrated and systematically characterized data of Barotse's land types apart from Piotr Wolski's remote sensing work from 1996 delineating hydrotopes (areas with similar hydrological responses). To close this knowledge gap, in 2014, our multidisciplinary team got busy: we conducted field work and engaged local men and women in participatory mapping activities, focus groups discussions, field visits and farming systems characterization.

Using what we learned, we produced infographics that depicted general land unit characterizations, planted crops, general soil characteristics and ecosystem services that are provided by 19 land types. This has been an excellent tool to translate local knowledge and make it accessible to the diverse stakeholders involved in agriculture, livestock, conservation and health.

The challenge this year was to use the previously collected information and try to map the nineteen land types using the freely available Landsat 8 Enhanced Thematic Mapper images from 2014. With the support from the University of Wageningen, my colleague Trinidad del Rio, together with stakeholders including local communities, governmental organizations and NGOs extrapolated the local typology across the floodplain. This is in essence, the first map of the Barotse land type use that has ever been developed – its thus a socio-ecological map rather than a purely ecological, hydrological, or land use suitability map.

We are now using it with our partners on the ground to explore scenarios that assess, firstly, the capacity of the landscape to provide diversified and nutritious food that nourishes local communities particularly during food scarce months, and secondly, to make evident the trade-offs and synergies, at farm and landscape scale, between livelihoods, nutrition and ecosystem services, in a language that local farmers and communities understand and can embed in their planning processes.

BI: In Barotse, on one hand you have been talking to men and women about their farming practices, on the other you are studying their landscape from an ecosystem services point of view. Where is the link between making a map of a landscape and improving peoples' diets?

BI: In Barotse, on one hand you have been talking to men and women about their farming practices, on the other you are studying their landscape from an ecosystem services point of view. Where is the link between making a map of a landscape and improving peoples' diets?

Natalia: I don't see it is just as a map, I see it as a 'Knowledge Translator' that can be used to work with the communities to understand and model the interests, perceptions, opportunities and challenges that local communities and stakeholders face in the Barotse floodplain for sustainable food production.

Just to clarify, we are scientists working on research in development. We do not give 'recipes' or tell people what is best for them. Our multidisciplinary team works in a participatory way. We actively engage local communities in our research and make them part of the learning process. We deliver and identify outcomes based on needs of the local community and their specific environmental and social context. This integrative, systems-based, multi-disciplinary and multi-scale approach takes us several steps closer to finding proper 'win-win' situations with the communities to improve their diets while guaranteeing the provision of critical ecosystem services.

For the future, communities in the Barotse envision improved crop and livestock production and productivity, nutrition, technology, access to markets, water and sanitation, infrastructure development and natural resource management. Is for this reason that we are exploring options with them to identify where and how crop production can be improved, which crops can contribute to reducing the nutritional gap, when and how these crops are most needed and where we can target crop diversification without compromising the provision of other ecosystem services critical to community well-being.

BI: In the Barotse map, most of the image seems to be comprised of Mushitu and Mulapo (green tonalities) and water - are those different land types and how you tell us a little bit about how men and women use them in their daily lives?

Natalia: Yes, they are different land types: Mushitu is a type of dry forest in the upland and Mulapo is a flooded grassland in the plain and the upland. The commonality between those land types is that both have natural vegetation and provide the bulk of ecosystem services critical for local communities such as soil fertility, drought control, wildlife habitat, pest control, firewood and charcoal, materials for crafts or ornamentals, agriculture and/or construction. In addition, both land types are good for agriculture and therefore the natural vegetation is commonly converted to agricultural land, Matema and Sitapa, respectively.

We identified four water related elements that are vital for local communities: canals, river, permanent ponds and temporary ponds (which dry out during the dry season). Depending on where one lives along the floodplain, the different water bodies provide water for agriculture, human consumption, spiritual and recreational activities, or fishing.

There has been a lot of focus on better understanding the role of gender in agricultural and rural development projects. Here we found important differences, particularly in two aspects: fishing activities and crop cultivation.

Women tend to fish in canals, ponds and smaller and shallower streams while men prefer to travel further afield to catch bigger fish in the river and deeper water. The fish caught by men and women has different purposes (e.g. smaller fish are often used for household consumption), market access and price.

Also, during the characterization of the land types, women mentioned more crops classified by nutritionists as dark green leafy vegetables, nuts and seeds, other vegetables, legumes and sweets. This indicates that women are central to ensuring household dietary diversity, where as the men may play a more central role in economic security. We still lack research to better understand how these gender specific roles interact within households – however by mapping these roles spatially, we are much closer to adapting crop cultivation practices to those roles.

BI: How do you think other researchers, extension workers and policymakers should use this research and these kinds of maps – both in Zambia and elsewhere?

Natalia: The map is a tool, normally used very early in the assessment phase of integrated landscape planning. Our focus on combining a participatory approach with remote sensing and spatial maps is enabling us to simultaneously articulate community priorities and visions, while scaling these vision and testing how they interact (trade-offs and synergies) with other interests in the region.

The map should be a tool for people in all types of positions to visualize land from a new perspective that takes into account environmental, social and agricultural aspects to facilitate and hopefully catalyze well-informed change. This tool will also help our research to focus on aspects important and relevant for local communities such as identifying, testing and assessing on the ground more varied, healthy and efficient production and provision of ecosystem services.

From a technical point of view, the map serves as the base layer for a new tool which will be launched at ESP8 on Thursday - Mapping Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being (MESH) - which will come in handy to translate the rather biophysical elements of the Barotse map into measures of well-being.

We welcome local partners, universities, NGOs to join us and get involved in our journey in Barotse Land.

~~~

On Monday, 9 November, at the 8th annual Ecosystem Services Partnership conference, Bioversity International researcher Natalia Estrada-Carmona will 'transport' the attendees to Zambia. During the 'Ignite ecosystem services and poverty alleviation with new approaches' (Session O5) she will describe the trade-offs and synergies between sustainable food production and other critical ecosystem services for people living in the changing and dynamic Barotse Floodplain, Zambia.

Follow the conference live on social media via #ESPConf8

This work contributes to the following CGIAR Research Programs: Agriculture for Nutrition and Health and Aquatic Agricultural Systems.

Photo: The sun sets as men fish in a lake in Barotse, Zambia. Credit: Bioversity International/N. Estrada-Carmona