Blog Looking for water in Jamaica’s Southern Plains

The Caribbean island’s breadbasket needs water. When major irrigation projects come online soon as expected, farmers, government and scientists hope to make the region reach its productive potential as it deals with intensifying effects of climate change.

Part 1

Comma Pen, Jamaica - Elica Sinclair’s crops had a rough December. Instead of towering over her head as usual, her sweet pepper plants barely reached her knees. Much of the fruit, her main cash crop for the season, were undersized or dying from diseases. Many flowers withered under the blazing sun and the mite-stricken leaves were in dire need of some expensive pesticides.

It didn’t have to be that way.

The Parish of Saint Elizabeth, in the Caribbean nation’s south, is widely considered the breadbasket of Jamaica. But erratic rainfall and hotter dry seasons, two products of climate change, are hammering farmers across the region.

Elica Sinclair with her sweet peppers in December 2021.

A disease-damaged pepper on Elica’s farm in December 2021.

“I’ve seen changes in the weather and the climate for the past 20 years,”

said Elica (pronounced e-LEE-sha), who grows a large enough variety of fruits and vegetables to fill half the produce section of a supermarket.

Soil on her farm used to be moist, even during the dry season. No longer. Yields have fallen. Buying water, delivered by water trucks, is too expensive to keep her whole field healthy and productive. She’s made some adaptations, such as planting crops at uncustomary times to align with erratic rainfall. But “basically, we can't do much because this water is the main ingredient to farming … and we don't don't have any running water.”

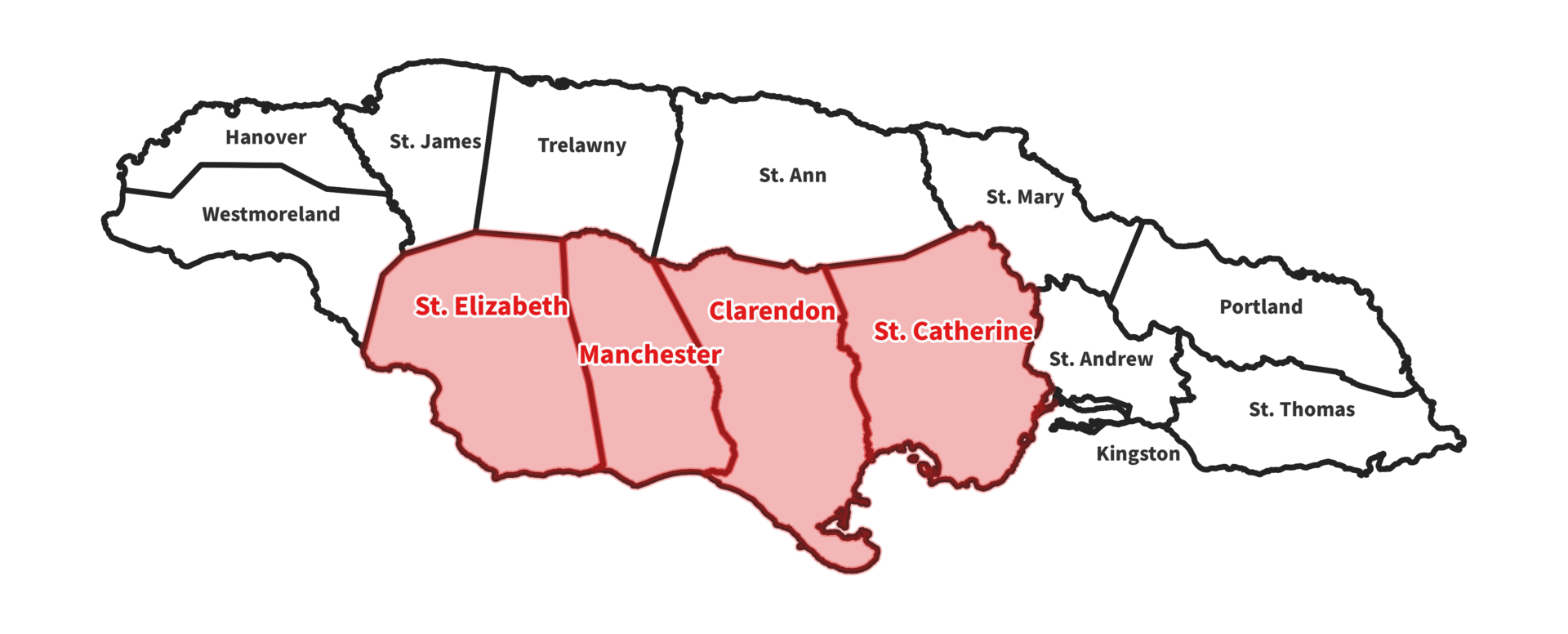

Map: The Southern Plains region of Jamaica.

Major new irrigation projects are expected to alleviate some of the stress of drought but agricultural experts say that fixing the breadbasket is more than a question of just adding water.

Irrigation will need to be properly managed and distributed equitably. More water could incentivize more production, which could put natural ecosystems at risk of being destroyed for agriculture. And increased production will lead to more demand for water. It is unclear as of yet if the new supply will meet it.

Even with better access to water, hotter dry seasons will require hardier plants. Some farmers may need incentives to change to different crops. Mitigation techniques will be needed to save harvests from torrential downpours. Farmers in the region will need to better organization to efficiently use pesticides and fertilizers to safeguard both the environment and their neighbor’s fields.

The good news is that Saint Elizabeth’s farmers are some of the kindest, resilient and most optimistic people I’ve ever met. Their stories and the experts who have been working with them over the past decade suggest that producers on Jamaica’s Southern Plains may become an Caribbean-wide example for handling the scourge of climate change.

“As farmers, we’re resilient. We are tough people,”

said Hendrick Francis, who produces vegetables. “We love what we are doing. What we are doing is a business and we treat it that way. We are hoping and trusting some time will come (when) we’ll be more productive.”

Work with farmers or fail

Donovan Campbell, of the University of the West Indies (UWI), and Anton Eitzinger, of the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, have worked with Jamaican farmers for a decade.

Donovan and colleagues from UWI work to understand the human side of farming - how communities work, what farmers consider best practices, and how men, women, youth and the disabled interact with their fields, each other, and the local economy.

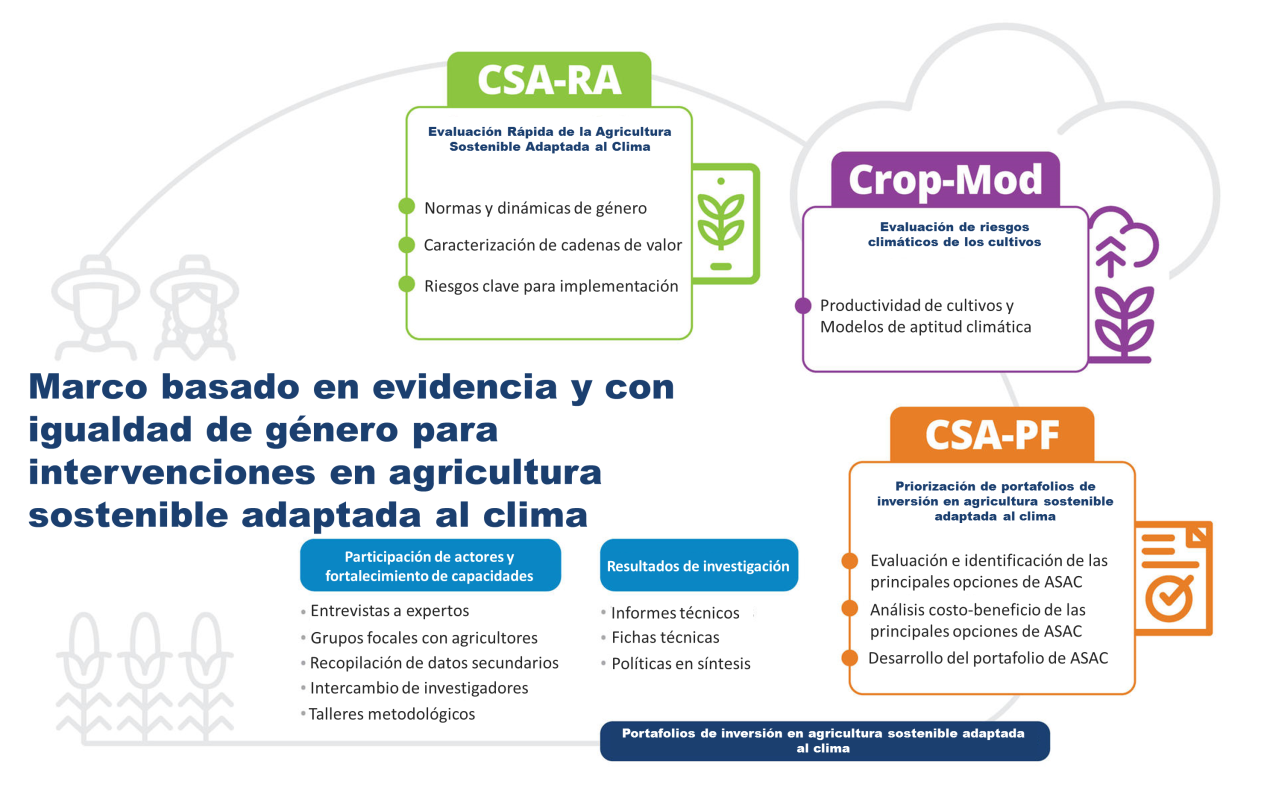

Anton and colleagues at the Alliance have developed crop models - essentially projections of how climate change will alter environmental conditions conducive for growing crops. They collaborate with UWI, donors and the Jamaican government to develop realistic climate-smart agriculture (CSA) recommendations.

The research team works on climate-smart agriculture field guides late one night in December 21. Left to right: Donovan Campbell and Jhanell Thomlinson (University of West Indies) and Anton Eiztinger and Miguel Lizarazo (Alliance Bioversity International and CIAT).

Farmers are crucial to the process. Without their input, the Alliance-UWI collaboration would likely be in the overfilled pantheon of well-intended, but ultimately misguided, development failures by now.

While major infrastructure projects are important to helping farmers, top-down approaches can fail if farmers are not involved in the process. Even in a region like Saint Elizabeth where there is one major problem - lack of water - affects everyone more or less equally, microclimatic conditions that vary across short distances and the subtle differences in production goals of each farmer mean every farmer will have to manage their resources differently.

“We make a mistake if we assume that the measures we're going to implement adapt to climate change will be appropriate for every farmer,” said Donovan, who worked on his Ph.D. thesis a decade ago while living with farmers in the region. “A one-size-fits all approach does not work for our farming systems in this region."

“Small farmers are at the frontline of some of the most serious threats and impacts from climate change. And they are the ones we expect to put measures in place,” he said. “They need to be involved in designing the plans that we hope will help them deal with climate change impacts.”

Donovan Campbell, of the University of the West Indies, speaks during a farmers workshop in Lititz, Jamaica in December 2021.

During their December field trip to Jamaica, Alliance and UWI researchers, and other local partners, led several workshops with farmers to the publish climate-smart investment profiles (which provide suggest where the best return-on-investment is for CSA spending), and climate-smart agriculture guides for farmers and extension agents to implement in the field.

This infographic covers the framework used to develop the CSA guides for Jamaica’s Southern Plains. Courtesy of Anton Eitzinger.

To learn more about the collaboration with farmers, check out these interviews with Anton and his Alliance colleague, Miguel Lizarazo.

Climate awareness now

During Anton and Donovan’s earliest research visits to the Southern Plains, climate change wasn’t on many farmer’s minds. Similarly, the plight of small-island states, which contribute virtually nothing to climate change but will suffer some of the worst consequences, was only beginning to get international attention. This has changed.

“What I can see now as a personal experience is that farmers are more aware enough about climate change,” said Anton. “They recognize that it's really an issue for them and they need to do something about it right now.”

Anton and colleagues’ early work on crop modeling has so far proven quite accurate. Tied to climate projections made by the Intergovernental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the modeling found that some crops, such as sweet potato and groundnut are more suitable for future climate conditions. In contrast, crops such as onions will depend more on irrigation, which will be crucial to higher yields for most of what is produced in the Southern Plains. Interviews with farmers show that these things are already happening, said Anton. Given the pace that climate change is advancing, the impacts will almost certainly get harder to deal without immediate action.

“Climate change is getting worse, and farmers can already feel it,” Anton said. “We have talked to many farmers and they confirm what we found in our models. They need to really rely on irrigated water to maintain the productivity of the plants.”

Farmers and authorities are willing to make changes. Among the realistic actions that could be implemented in the short term, the Alliance and UWI recommended:

· Creating incentives for climate-smart farming

· Developing farmer field schools to share knowledge and teach skills for CSA

· Building platforms for peer-to-peer knowledge exchange among farmers

· Improving water efficiency through smart innovations such as increased water harvesting and drip irrigation

· Creating and promoting access to financial mechanisms for implementing climate-smart investment portfolios

· Developing regional hubs for food systems that provide farmers with options of product processing for added value such as food packing facilities.

Based on interviews with farmers, government officials and farming group leaders, the recommendations were well received. In the coming months, producers and extension agents will be working on implementing many of these tasks.

Some activities will require as-of-yet unsourced funding - lack of access to credit is a top concern among farmers after climate change - but many can be implemented just by modifying some current practices. Several CSA activities are already routinely used by farmers. This is encouraging for the prospects of CSA adoption at scale. Many farmers harvest rainwater and covering fields with guinea grass, which helps retain soil moisture.

“When we talk about climate smart agricultural practices, most of it is not new,” Donovan said, pointing to practices like mulching and covering fields with grass to retain soil moisture.

“But the problem is, because of climate change, some of these practices are not as effective as they used to be. This is where the scientific knowledge comes into play and has to be twinned with the local knowledge and practices. Farmers are willing to learn … and they're also willing to teach others about their experiences, and how some of the decisions that we're making higher up can be more effective on the ground.”

Wiston Coff, 69, a farmer in Jamaica’s Southern Plains, spreads Guinea grass to retain moisture in a field.

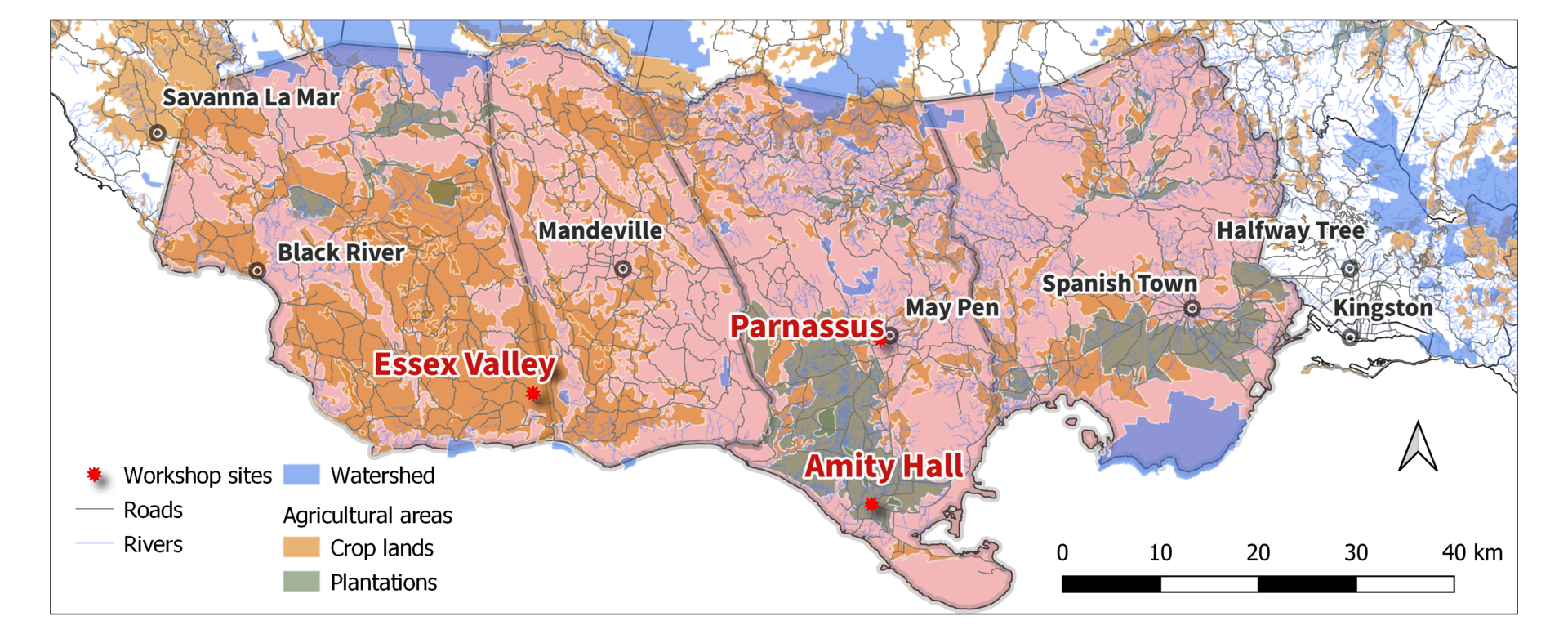

In 2019, the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) allocated funds from the United Kingdom Caribbean Infrastructure Partnership Fund to assist the Government of Jamaica in financing agricultural development projects. These targeted communities in Parnassus and Amity Hall, and built on the on-going Essex-valley Agricultural Development Project which seeks improved irrigation and climate resilience measures for farmers.

Regional map showing research and workshop locations.

For now, however, more water is what’s needed most. Today, a regional network of mostly freelance water trucks fill up tanks and delivers water to fields. While the water is free, delivery is not. And many farmers can’t afford enough to keep their fields properly hydrated.

Stay tuned for the second part of this series to find out more about how farmers attain water today during the dry season and what the government and others are already doing to scale up climate-smart agriculture practices across Jamaica.

Credits

Writing and photography: Sean Mattson, Alliance

Photography editing: Daniel Gutierrez, Alliance

Jamaica Acclimatizing video & filming: AfroAsian Productions, Jamaica

Video editing: Alejandro Marulanda, Alliance