From the Field Unpacking Identity and Intersectionality in India’s Assamese Small-grower Tea Sector

Explore Northeast India’s complex tea value chain, and the lives of the women behind each harvest, with this photo story by our researchers.

By: Haley Zaremba and Meghajit Shijagurumayum

Do you know where your tea comes from? Recent reports on the state of the industry have shown that there is cause for concern about whether your cup of tea was produced ethically, particularly if those leaves came from India.

Worryingly, these results pertain to tea plantations, which are a highly regulated sector with established worker protections. But there is another, less formalized side of the industry run by small tea growers not associated with plantations that are even more vulnerable to exploitation and hardship. The market share of small tea growers in India has reached around half of all tea production as low leaf prices push the tea sector to become increasingly informal. The people who are employed in this small tea growing sector, and particularly those from marginalized groups, are particularly vulnerable to exploitation as their work is often invisibilized and unregulated.

While the rise of the small tea sector is fairly well documented, there is extremely little evidence about who is conducting this small-scale cultivation, what their roles are, and the status of their working conditions and economic opportunities. Who are these invisible workers, and what can be done to safeguard their livelihoods and reduce exploitation?

Field study: the faces behind Assam’s tea production

To answer these questions, we look to the northeastern Indian state of Assam, where these issues are particularly pronounced. Assam is the is the the biggest tea producer in India, representing over half of national tea output, and has the most registered small tea growers of any state. Recent research by the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT in the tea-growing region of Assam sought to understand who are the faces behind each cup of tea, and how their positions in the value chain could be made more visible and improved.

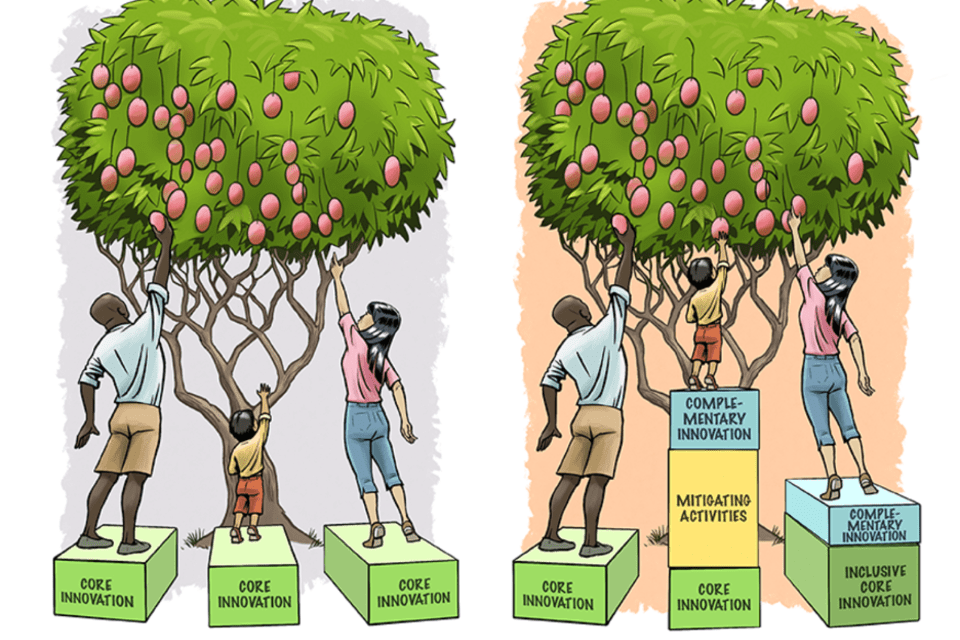

Researchers found that workers from ethnic minority groups, and particularly women, are highly vulnerable in the small tea sector, easily exploited by middle-men and often operating at a loss. The experiences, acess to benefits, and level of empowerment of these workers are highly mediated by their intersectional identities – most notably gender, ethnicity, and caste. Yet, intersectionality is often overlooked in agrifood value chain development initiatives and policies.

Generally speaking, high-caste ethnically Assamese men tend to work at more formalized, higher skilled, and better remunerated parts of the value chain, and are more likely to have a voice in decision-making spaces, such as tea collectives and stakeholder meetings with the Tea Board. At the opposite end of the spectrum, low-caste “Tea Tribe” women (an ethnic minority brought to Assam by the British to work on conial tea plantations) tend to work at the lowest, most drudgerous, and least remunerated nodes of the tea value chain, and have very little access to or knowledge of decision-making spaces.

This photo essay seeks to make these invisible workers visible and to give voice to their distinct experiences.

An ethnically Assamese woman stands in front of her family’s tea field. She’s from a financially secure family, and does not need to work on the land herself. Instead, she and her husband hire out Tea Tribe women and men to work the field. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

This group of ethnically Assamese women lacks the means to hire outside labor on their households’ tea fields, but they own enough land and are financially secure enough that they do not need to work for the tea plantations. Instead, they work on each others’ fields in rotation, and say that they are happy they don’t have to deal with the stress and long hours of plantation work. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

A Tea Tribe woman greets researchers at her home after a long day picking tea at a nearby plantation as a wage worker. She plucks plantation tea six days a week and plucks her own tea on the seventh day to supplement her small income. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

Poor road conditions and a lack of infrastucture characterize the area that the above Tea Tribe woman and her family live and work in. They transport their plucked leaf via bicycle down this rutted road to sell to an agent. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

An agent stands in front of leaf he has grown on his own land and bought from small tea growers, which he will sell to a bought leaf factory. Small tea growers depend on these agents for cash advances, but often sell to them at a loss. There is no transparency about how or by whom these prices are set. These agents are almost exclusively men, and often come from the same community and ethnicity as the growers. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

A new truck and fresh paving sits in front of the agent’s tea operation, a stark contrast from the lack of resources and infrastructure seen nearby at the Tea Tribe community. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

A group of farmers meets to discuss forming a small tea grower coalition. Notably, nearly everyone present is male and ethnically Assamese, suggesting that the voices of women and ethnic minorities are relatively unheard in decision-making spaces around tea production. Photo credit: Haley Zaremba/Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

This case study of Assamese small tea sector workers is a perfect example of why intersectional approaches are so critical in agrifood value chain development. Cross-cutting identities such as caste, ethnicity, and gender are integral to the ways that small tea growers are able to participate in tea value chains, benefit from the tea they grow, and have a say in their own livelihood strategies. An intersectional lens is essential to understanding the nuances of this invisibilized sector and to identify just development pathways to improve the livelihoods of the most marginalized producers and traders. Centering women from low castes and ethnic minorities as protagonists in value chain development initiatives is an essential first step to making sure that every cup of tea is ethically and responsibly sourced.

This research was conducted as part of the CGIAR Initiative on Gender Equality, with support from the CGIAR Trust Fund Donors.