Blog Opportunities for all: How the Healthy Landscapes project is improving rural livelihoods in Sri Lanka

The rehabilitation and sustainable management of Village Tank Cascade Systems - the primary focus of our Healthy Landscapes Project - is also consistent with national development priorities in food security, livelihood improvement and rural poverty reduction. What would this look like for an average family? Keep reading for an example.

By Sharon Mendonce, Thejana Bandara and Sujith Ratnayake

It’s dinner time in the Gamage* household and Sherangi*, a talented home cook, has prepared a special meal in celebration of her daughter Devindri’s* 18th birthday. While a few of her favourite dishes are on the table, unfortunately several are missing. Like many other Sri Lankan families, the Gamage household has had to cut their grocery list short as a result of limited purchasing power and high food prices.[1]

Sri Lanka is currently experiencing its worst economic crisis since its independence in 1948.[2] The crisis has doubled the poverty rate from 13.1 to 25.6 percent between 2021 and 2022, increasing the number of poor people by 2.7 million.[3] While agriculture remains the backbone of the economy, and 82 per cent of the country’s total population resides in rural areas, almost half of the rural poor are small-scale farmers.[4] Sherangi’s husband, Dinushan*, is one of them.

*Disclaimer: The characters portrayed are fictional, and any resemblance to real persons is completely coincidental.

The Gamage family lives by the Mahakanumulla Village Tank Cascade System (MVTCS) in the Anuradhapura District of the North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Dinushan cultivates maize on a 2 hectares large, rain-fed land near the MVTCS. Unfortunately, a recent increase in dry spells within the region is putting cereal (like Dinushan’s maize) and other harvests at risk; making it more difficult for him, as well as other farmers who depend on the MVTCS for irrigation of their farms, to earn a living from farming and provide for their families. Indeed, while the Village Tank Cascade System (VTCS) was developed many centuries ago to provide an adequate supply of water for agriculture and livelihoods in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka, as we saw in the previous blog, it is facing multiple threats.

The Climate-Biodiversity-Food and livelihood nexus

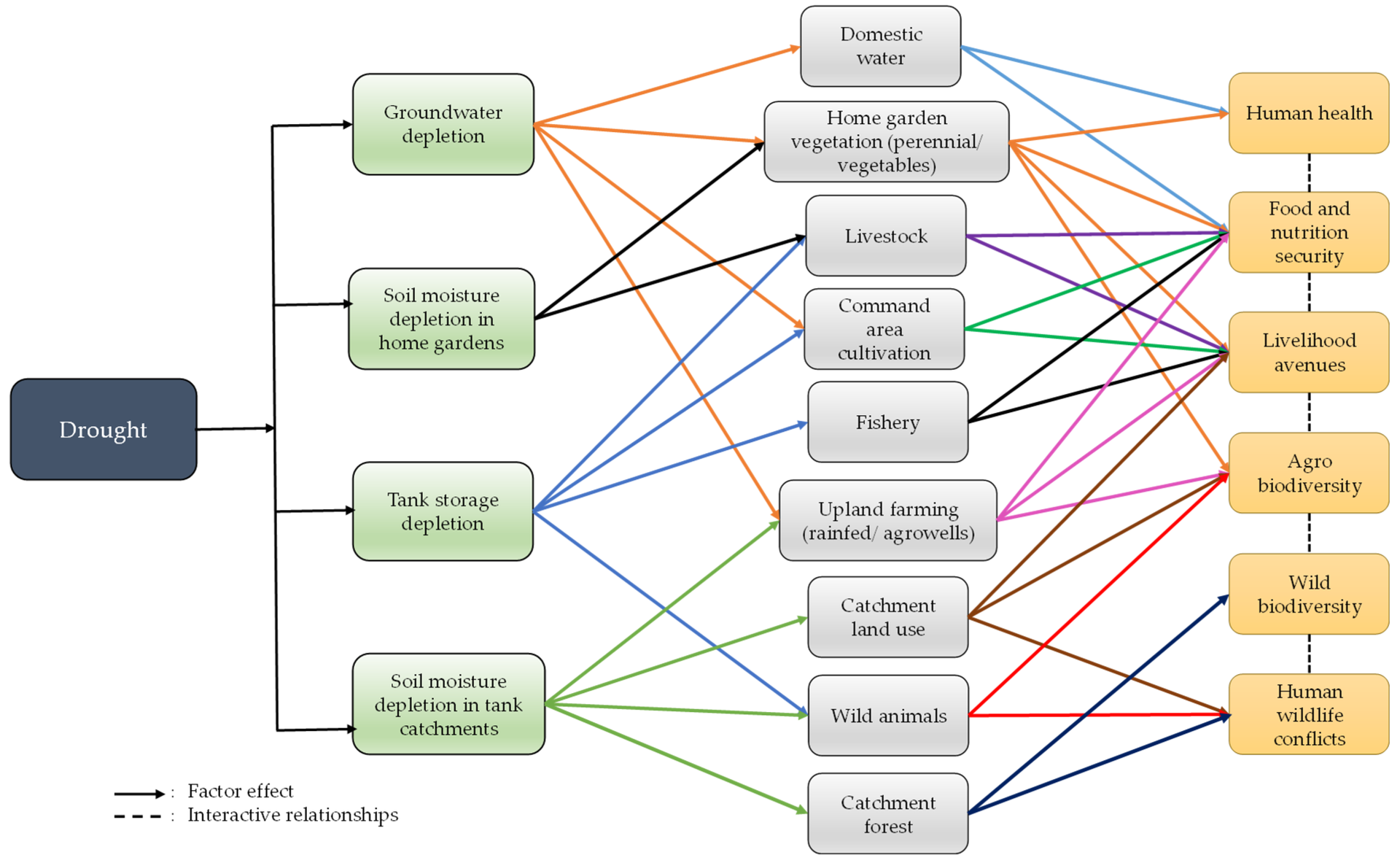

Studies and participatory research carried out in VTCSs, including baseline assessments undertaken as part of the Healthy Landscapes Project’s (HLP), have enabled the formulation of a Climate-Biodiversity-Food and livelihood nexus in the MVTCS. The nexus, which is featured in a research article titled “Sustainability of Village Tank Cascade Systems of Sri Lanka: Exploring Cascade Anatomy and Socio-Ecological Nexus for Ecological Restoration Planning”, shows the potential impact of climate change and recent changes in VTCS land uses on ecosystem health (agrobiodiversity and wild biodiversity) and human well-being (human health, food and nutrition security, livelihood avenues, and human-wildlife coexistence).

Figure 1: Climate-Biodiversity-Food and livelihood nexus in the Mahakanumulla VTCS (Source: Ratnayake, S.S.; Kumar, L.; Dharmasena, P.B.; Kadupitiya, H.K.; Kariyawasam, C.S.; Hunter, D. Sustainability of Village Tank Cascade Systems of Sri Lanka: Exploring Cascade Anatomy and Socio-Ecological Nexus for Ecological Restoration Planning. Challenges 2021, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe12020024)

Climate change increases the likelihood of extreme climatic events- a particular cause of concern in Sri Lanka’s Dry Zone, which already receives the lowest annual rainfall of the country. As seen in Fig. 1, droughts would mean drier soil and a decrease in water stored in tanks. This could have an incredibly negative effect on livelihood avenues (such as farming, livestock, fishery etc.) that depend on these sources of water. However, addressing the impacts of climate change on VTCSs and the ecosystem services they provide, can help protect the livelihoods of cascade landscape communities. For example, despite evidence of climate change between 1961-2010, the composition of home gardens in Sri Lanka had not changed substantially over the period. Strategies adapted by home gardeners (e.g., changing the planting dates of the crops) had enabled them to cope with changes in climate and ensure food security.[5]

At a crossroads

For Devindri, turning 18 means it’s time to make some important decisions about her future. She could follow in the footsteps of her father, however like him, she’s been seeing the increasing effect of climate change on their farm and she’s concerned that this worrying trend is not going to be reversed anytime soon. Over the past few years, she’s also noticed that many students leave Mahakanumulla once they complete high school. Indeed, a marked decline in agricultural profitability and traditional livelihoods have been encouraging out-migration (especially of youth) in search of economic opportunities elsewhere. She wonders if this could be an option for her.

Safeguarding futures

While the Healthy Landscapes project targets the rehabilitation and sustainable management of VTCSs, the project is also consistent with national development priorities in the areas of food security, livelihoods and rural poverty reduction.

Youth unemployment is a major challenge in Sri Lanka, as young people face unemployment rates more than three times higher than for the population as a whole.[6] Diversified smallholder vegetable or fruit systems are important pathways for young people, like Devindri, to be engaged in agriculture. In fact, rainfed areas of the cascade landscapes are emerging as sites where young people (with necessary investments in the form of dug wells, drip irrigation, and tree seedlings) can demonstrate their entrepreneurial skills. The HLP is advocating for these rainfed (or Chena) lands to receive more attention in efforts to help raise incomes through biodiverse small farms especially for young people.

The project also recognizes the significant impact climate change has on livelihoods in cascade landscapes (such as Dinushan’s) and is working towards a future where VTCSs can play a major role in climate change adaptation, particularly since the VTCS was designed by the country’s ancestors to address drought.

A modern chili farm which has implemented smart farming technologies (e.g., drip irrigation and poly mulch system for better management of water and weeds) was visited by farmers, Provincial Department of Agriculture officers and HLP staff late last year. Such exposure visits introduce farmers to modern agricultural practices that can help them adjust to or even take advantage of the impacts of climate change. (Photo Credits: Audio-Visual Centre, Department of Agriculture/ P.Ranathunga)

The HLP is also looking to set up food stalls called ‘Hela bojun’, which offer people access to traditional, nutritious and safe meals at reasonable prices. By providing courses on food preparation, food hygiene, customer care and business management The Women’s Agriculture Extension Programme, under Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Agriculture, has facilitated the creation of a network of Hela bojun across the country. These food stalls have shown great potential for empowering rural women, promoting entrepreneurship, food biodiversity and traditional food culture.

Taking up a job at the soon to be established Hela bojun could give Sherangi an opportunity to share her culinary skills with a broader audience, while simultaneously earning a living. Some women operating such food outlets have become the main breadwinners in their families, earning a living wage of USD$600–800 per month! Additionally, with the Hela bojun likely to create market demand for traditional ingredients (e.g., jaggery, chilies and bananas) and the HLP also planning to include vegetable stalls so consumers can easily buy fresh, organic produce, the Hela bojun is an opportunity to support smallholder farmers and help them overcome market entry problems.

Sri Lankan culinary tradition and food culture is rich and currently reliant on and influenced by the rich agrobiodiversity associated with family farms, home gardens, and forest ecosystems. Does this translate into healthy diets for cascade landscape communities? Find out in our next blog.

References

[1] Remote Household Food Security Survey Brief-Sri Lanka, Oct 2022, WFP

[2] Country Brief-Sri Lanka-Nov 2022, WFP

[3] Sri Lanka Development Update-Oct 2022, World Bank

[4] Sri Lanka-Country Profile-IFAD

[5] Weerahewa, J. et al. Are homegarden ecosystems resilient to climatic change? An analysis of adaptation strategies of homegardeners in Sri Lanka. APN Science Bulletin, 2(1), 22–27. doi:10.30852/sb.2012.22

About the Project

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), the world’s largest public funder of international environmental projects, is supporting the Healthy Landscapes project led by Sri Lanka through the Ministry of Environment as the Lead National Agency. The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT is coordinating the project with implementation support from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).