Blog Building back better: the ecological restoration of Sri Lanka’s Village Tank Cascade Systems

Village Tank Cascade Systems have supported many generations of communities by providing multiple ecosystem goods and services- from nutritious food to a scenic space. However, today these systems are at risk. Read on learn about the threats and how the Healthy Landscapes project is addressing them.

By Sharon Mendonce and Sujith Ratnayake

Our previous blog introduced some of the many goods and services provided by Village Tank Cascade Systems (VTCS). By working harmoniously with nature, ancient communities were able to develop a rainwater harvesting and management system that helped to meet their needs and those of future generations. For example, they established tanks and paddy fields in low-lying valleys, where clayey soils with poor drainage had limited use other than paddy cultivation. They also maintained watering holes for wildlife so that animals would be discouraged from entering human-managed areas, thus reducing the risk of crop damage, human-wildlife conflicts and deaths.

Threats to the ancient Village Tank Cascade Systems

Unfortunately, there are multiple threats to the sustainability of VTCSs, as well as the ecosystems and biodiversity that underpin them.

“Today, we do not see the original landscape attributes of the ancient VTCSs. The food systems, traditions, aesthetic beauty and cultural values that were once embedded in these systems have already been depleted or are in the process of deterioration because of neglect.”

says Mr. R.M. Jayathialake, a senior village member, farmer and community leader.

Over the past few decades, changes in the manner in which productive land is used for agriculture, over-reliance on agricultural pesticides and overuse of subsidized fertilizers in cascade landscapes has led to poor soil health and pollution of drinking and irrigation water. Amongst other effects, this has raised challenges in agricultural productivity, resilience and ultimately profitability, while also impacting community diets, livelihoods and even out-migration (with it a loss of traditional knowledge, awareness and appreciation of cascade landscapes). Worsening these threats to VTCSs are climate shocks, such as an increased severity of droughts and oversights by some VTCS restoration projects (e.g., restoring a single tank without considering its function as part of a cascade system.)

Engaging local communities for successful ecological restoration

One way of avoiding oversights in restoration projects is by involving local communities and using their rich traditional knowledge in project planning and implementation. Local community input is particularly important in the case of VTCSs restoration as the ecosystem goods and services they provide are the result of centuries of successful interactions between the cascade landscape’s people and its other components such as its plants, animals, rocks, soil, water and climate.

Considering its importance, local community input was a crucial part of baseline research for the Healthy Landscapes project. As highlighted in a research article titled, ‘Land Use-Based Participatory Assessment of Ecosystem Services for Ecological Restoration in Village Tank Cascade Systems of Sri Lanka, local knowledge was combined with expert judgements, estimations of land degradation and biodiversity of various land use systems to assess the multiple ecosystem services provided by the Mahakanumulla VTCS (MVTCS) located in the Anuradhapura District of Sri Lanka. The MVTCS has 28 village tanks and serves 3,432 inhabitants.

Village Tank Cascade Systems provide multiple ecosystem services. The Healthy Landscapes project is working to optimize the provision of many of these services while being cautious to do no harm to others. (Figure credit: Healthy Landscapes Project/L.Pierotti) View full-size.

What is Ecological restoration?

According to the Society for Ecological Restoration, ecological restoration is the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed. The goal of ecological restoration is to return a degraded ecosystem to its historic trajectory, not its historic condition.

For VTCSs, a return to their historic trajectory means not only a return to their status as a landscape that is rich in natural resources, harbouring many economically and ecologically valuable species and habitats; but also the optimization of the provision of its ecosystem services, which are important to meet the tangible and intangible needs of present and future generations of cascade communities.

In addition to highlighting the multiple ecosystem services of the MVTCS, community members (many of whom have been living in the VTCS for at least two generations) were able to identify the main plant and animal species that are linked to the cascade landscape's food provisioning and regulating services. For example, inland fisheries, which provide edible fish species for food and nutrition, depend on multiple species of fish such as the snakehead fish (Channa striata) and the tank goby fish (Glossogobius giuris). Similarly, pest and diseases outbreaks are regulated by insects such as dragonflies (that feed on mosquitos), and plants such as the antique spurge trees (Euphorbia antiquorum) whose fronds are spread over paddy fields to control small pests.

Considering the importance of biodiversity in the provision of ecosystem services by VTCS, there is an urgent need to address these multiple threats and recover what’s been lost.

Looking to the past for solutions for the future

The Healthy Landscapes project addresses threats to the rich biodiversity in the dry zone of Sri Lanka by rehabilitating and promoting the sustainable management of VTCSs. In doing so, it revives degraded ecosystems and enhances their provision of valuable goods and services.

Setting the groundwork for ecological restoration, the project has set itself the goal of renovating the traditional physical features of multiple VTCSs. In the case of one tank, simply repairing its bunds will allow it to be flooded again, restoring over 300 acres of paddy fields within just a year- that’s about the size of over 150 soccer fields!

The Healthy Landscapes project has already begun renovation of the Thumbikulama tank that was destroyed by a natural disaster thirty years ago. (Photo credit: Provincial Department of Agriculture/W.Kaluarachchi)

The Healthy Landscapes project also aims to promote the use of local, underutilized, climate-smart and nutritious agrobiodiversity in home gardens, family farms (especially the rainfed uplands), and in other areas around the restored tanks. This includes cereal crops (e.g, finger, foxtail and kodo millets), legumes (cowpea, soyabean, and groundnut) and a wide range of fruit and medicinal trees. These cultivars have evolved over the years, growing despite challenging conditions and will likely be important to ensure the sustainability of VTCS, as well as build its resilience against future stresses and shocks. The project will use these cultivars to improve food and nutrition security and better livelihoods for local communities and beyond.

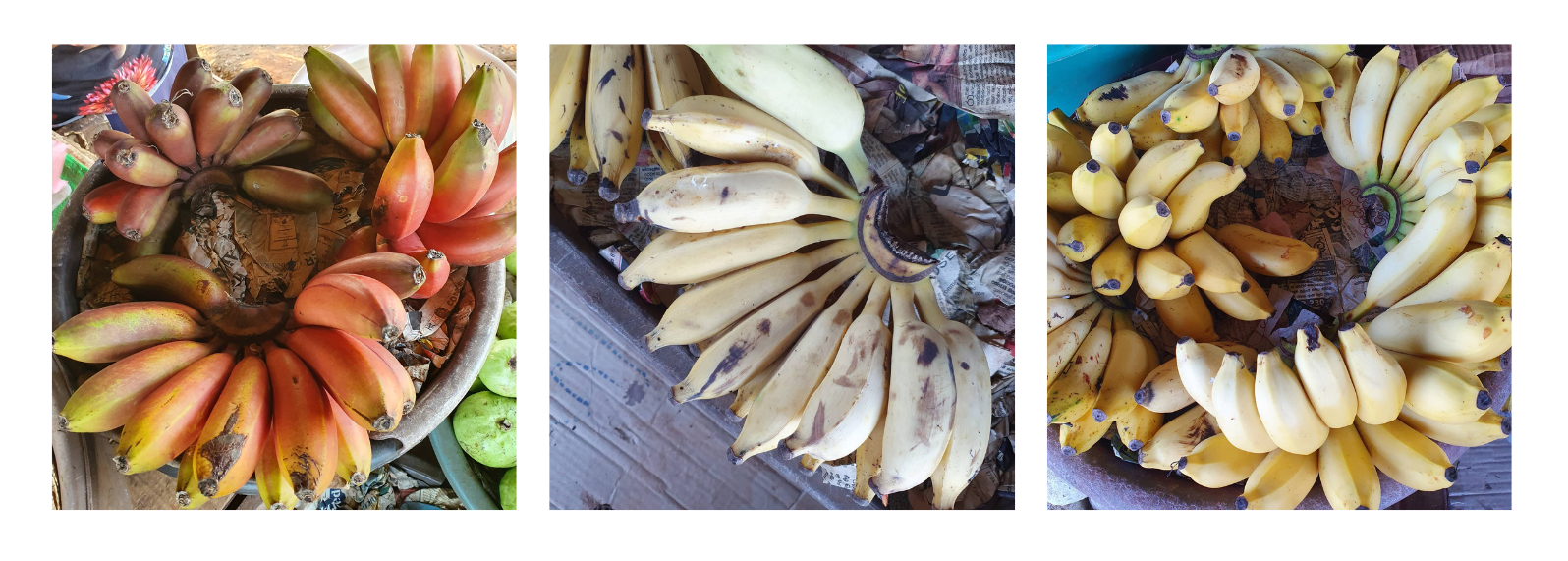

Multiple local varieties of bananas can be found in cascade landscapes. Besides a wide range of micronutrients, they often contain more beta-carotene than the more common Cavendish variety. (Photo credit: J.Gonsalves)

As highlighted by Ratnayake et.al. 2022, it is important to remember that the success of the ecological restoration of VTCSs depends on the extent to which strategies address the diverse levels of cascade ecological complexity, as well as the social engagement of local communities. Stay tuned for our next blog in the series to find out more about how the Healthy Landscapes project’s ecological restoration efforts are empowering the cascade landscape community and strengthening their role as custodians of VTCSs.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), the world’s largest public funder of international environmental projects, is supporting the Healthy Landscapes project led by Sri Lanka through the Ministry of Environment as the Lead National Agency. The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT is coordinating the project with implementation support from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).