From the Field Transformed livelihoods empowering rural women in Rwanda

In April 2018, heavy rains pounded the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda with torrents of water washing down to Burera Village causing flooding and destroying property as they went along.

Xaverine on her wheat farm.

Ms. Xaverine Nyiransabimana, a widow, is one of the villagers whose house was destroyed by the rains. However, thanks to Participatory Integrated Climate Services for Agriculture (PICSA) she received from the Alliance of Bioversity and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), this one storm did not dash her hopes. Within a few weeks, Xaverine was back on her feet with a temporary house for her children. She is now in the process of completing the permanent structure that they are soon going to occupy. In 2016, Xaverine was among the first group of farmers in Kigote Village of Gahunga Sector trained by Joseph Munyanganizi, a farmer promoter under the Rwanda Climate Services for Agriculture Project.

“The four main steps in the training that stood out for me were how to give value to what you have in your home, how to plant in a line, how to use fertilizer and manure, and how to move from agricultural activities to other livelihood activities or even engage in both,” she tells me.

Before the training, Xaverine was a subsistence farmer who was engaged in planting wheat, beans, and potatoes. She goes on to tell me that she had no idea what quantities of water were required for different crops. After the training, she was able to understand that the amount of rainfall in her region was good for wheat and she channeled her efforts into planting wheat.

From her piece of land measuring 900 square meters, Xaverine used to plant 10 kg of wheat using the broadcast method of planting and she harvested 120 kg in return. However, after the training, she was keen to follow the planting times taking into account the climate information as advised and she planted 5 kg of wheat in a line using the required spacing as taught in the training. In addition, she applied manure combined with diammonium phosphate (DAP).

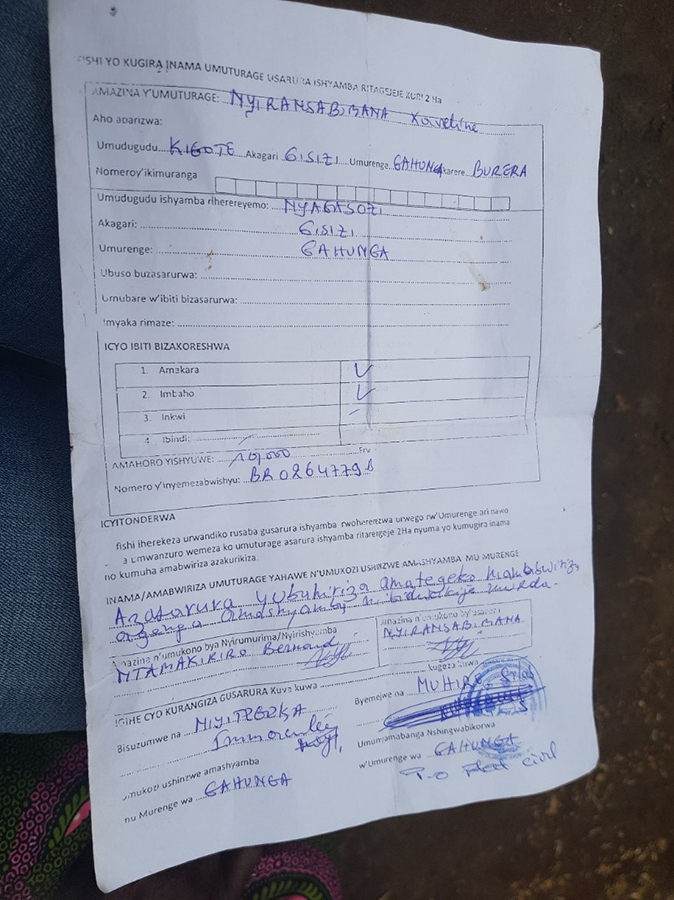

Come harvest time, she was able to harvest a total of 180 kg of wheat. Yvonne Uwase Munyangeri, a Project Assistant from the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT, says, “In the training, we teach them to calculate the profits after they deduct all the expenses.” In this case, she goes on to enumerate the cost of one kg of wheat seed at RWF 1,100, cost of labor at RWF 4,800, and cost of fertilizer at RWF 4,160, bringing her total investment to RWF 10,060. She sold 100 kg from her harvest and kept 80 kg for home consumption. Income from the sale was RWF 54,000, giving her a net profit of RWF 43,940.

“I am happy she used the organic manure, whereas other farmers opt to buy,” Yvonne adds. “If she had not kept her organic waste for manure, she would have had to buy about 100 kg of fertilizer and this would have reduced her profit.”

Xaverine extended the same techniques she learned to the other crops she was farming, beans and potatoes, before eventually giving up on the potatoes since they were not doing well.

“The water from the mountains washed away the soil, thus affecting the production of potatoes,” Yvonne confirms.

The beans, however, did well. Whereas initially Xaverine had planted 15 kg using the traditional method in which one uses fingers to put the seed into the ground without spacing, come harvest time she harvested 60 kg. After the training, she used a hoe, dug holes in a line, and applied the required spacing. She then planted 5 kg of beans and applied about 130 kg of organic manure and two kgs of DAP. As a result, she harvested 150 kg.

Livelihood Transformation

The training was not only limited to farming activities but was also extended to livestock management and livelihood development. Having experienced the benefits of the training in her farming activities, Xaverine now wanted to try her hand at livelihood and see what that could bring out.

As a start, she resolved to venture into selling firewood, having noticed that there was a huge interest from people and especially traders from her local shopping center who brewed beer. She committed to supplying their firewood needs. She started by purchasing trees ready for harvest and chopped them down for firewood for sale.

Xaverine bought five trees, which made two bundles of firewood for a total of RWF 10,000. She then employed labor that cost RWF 1,000, spent RWF 800 on transportation, and, after deducting these costs from her sales, she had made a large profit of RWF 28,000.

In 2017, Xaverine was at the local shopping center when she saw women selling charcoal and enquired how much it cost. To her surprise, 1 kg of charcoal was selling for RWF 250.

“I thought to myself, this is a lot of money, and I can make some selling charcoal,” she tells me.

Using her proceeds from two seasons of wheat (this was a span of two years) and together with the sales from firewood (RWF 50,000), she went to the village and bought a small forest that was ready for harvest. She hired four men for RWF 1,000 to cut the trees. They then dug a hole and put in the trees to burn charcoal to be ready in 15 days.

Xaverine’s investment cost for this project was RWF 58,000 and she was able to harvest a total of four sacks of very good quality charcoal and one small sack and six kg of small charcoal, which she sold off-site for RWF 200/kg. Her total income was RWF 90,000 and, after deducting the investment cost, she made a profit of RWF 32,000.

“For a trial, this paid off very well, and from there I started buying bigger pieces of forests,” she explains.

Xaverine does not like to think back to the pigs she lost during the flooding season. However, she went ahead and bought one pig and one lamb to replenish her stock and the pigs have since multiplied to 13. Xaverine is now constructing a good house that will withstand flood rains should any come in the future.

“I do not know how to say this,” she admits. “But this training was very important. Now, I think I have more value. When the disaster came, other people went to stay in schools because their homes were completely destroyed but I did not have to move as I was able to build my own house.

“I would therefore urge the farmers who have not yet gone for this training to please make sure they make time to attend,” she concludes.

With her accumulated profit, she went and bought a 13 m by 18 m piece of land in preparation for her charcoal business.

About Participatory Integrated Climate Services for Agriculture (PICSA)

The research department of Reading University in the United Kingdom designed PICSA. In 2016, CIAT in partnership with the Rwanda Meteorological Agency then adopted it for the Rwandan context and included the Rwandan climate and crops.

CIAT, in partnership with Rwanda Meteorology Agency and Rwanda Agricultural Board (RAB), a government institution, has a responsibility to train others in the country. The systematic training kicked off at the district level first by targeting agronomists and then cascaded down to socio-economists and development officers, sector agronomists, farmer promoters, and farmer field school facilitators. The training takes place five days a week (Monday to Friday) and targets farmers in groups in Twigire Muhinzi, an extension model. The project collaborates with local NGOs to help disseminate climate information.

“The main objective for this training is to ensure that farmers have access to climate information, understand climate patterns, and use this information in their farming plans. CIAT takes this information to the farmers because we have realized this information is useful when it is tailored to specific locations,” Dr. Desire Kagabo, coordinator of the Rwanda Climate Services for Agriculture Project, tells me.

Xaverine is a mother of seven children (two boys and five girls) from 14 to 36 years of age. She is a grandmother of 14 children and, even though she is a widow, she is now comfortable taking care of her family.

“Improved decisions toward crops, livestock, and livelihood are key objectives of the training and Xaverine has proved that community members can make positive impacts in their communities,” Yvonne concludes.