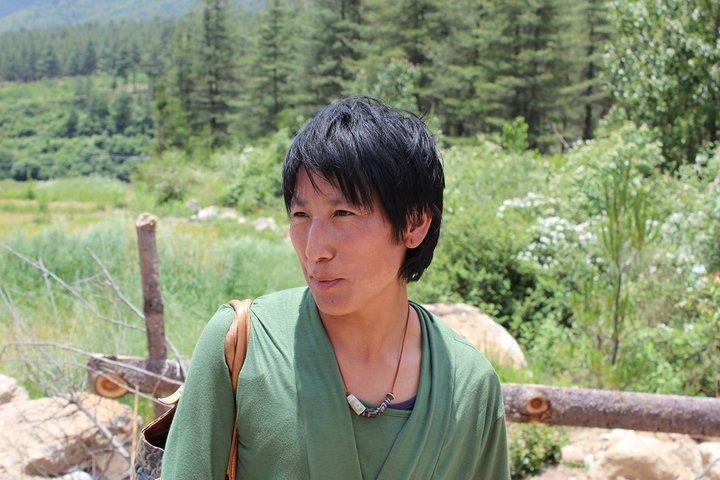

Rural Bhutanese farmer Pema faces climate change with a cornucopia of agricultural biodiversity

Rural women are integrally connected to all aspects of local biodiversity – as users, custodians and agents of change. On the occasion of the International Rural Women's Day, scientists Ronnie Vernooy and Lhab Tshering chat with Bhutanese farmer Pema, the first farmer to have a greenhouse in the village of Tsento, Bhutan.

Rural women are integrally connected to all aspects of local biodiversity – as users, custodians and agents of change. On the occasion of the International Rural Women's Day, scientists Ronnie Vernooy and Lhab Tshering, National Biodiversity Centre of Bhutan, chat with Bhutanese farmer Pema, the first farmer to have a greenhouse in the village of Tsento, Bhutan.

Pema lives with her parents, husband, and six-year-old daughter in a traditional Bhutanese farmhouse in the village of Tsento, Shari in the fertile Paro valley, in the central western part of Bhutan. There are about 50 households in the village located in the dispersed manner common to the country. Although the households are dispersed, and sometimes far from each other, throughout the year, agriculture continues to depend on cooperation among villagers.

"Right now is the rice transplanting season. Transplanting is done by teams of women. First, the men plough the land which is then flooded before transplanting. Neighbors work together to finish the work on time going from the fields of one household to the fields of another. Nowadays, most of the households cultivate a rice variety that was introduced in the area about 10 years ago. It is named 'Nepali'. It yields well and responds effectively to increased fertilizer use. Two other varieties can be found: 'Paro China' and 'Chadanath 1'. Before, we used to grow two traditional red rice varieties 'Kuchum' and 'Raynam', but these were affected by disease and decreasing yields. With government support, we changed our varieties. We're very happy with 'Nepali'," says Pema.

Farmers in the village are interested in growing new varieties, especially ones that adapt well to the changing environmental conditions. Pema points to a particular field in which 16 small red flags can be seen, "Right now, we have a small experimental plot with 16 new varieties introduced by the Renewable Natural Resource-Research and Development Centre of the government. It is the first time that we are testing these new varieties together with researchers. These varieties are supposed to do well in higher altitudes, respond better to dryer conditions, and have good disease resistance. We are pleased with this experiment. It is too early yet to identify the most promising varieties, but we hope that one or more will be successful. Then we intend to try them again in the next growing season."

Apart from rice for household consumption, Pema grows potatoes as the main cash crop. She also has a garden with several vegetables, such as beans, cabbage, spinach, broccoli, turnips, pumpkins, rapeseed, onions, mint, and some maize and a selection of herbs and spices. In addition, she has a small field where she grows drought and disease-resistant oats (which she uses for fodder), several fields with various types of chili peppers (for home consumption and for the market), and an orchard with apples and peaches. The Bhutanese love chili peppers and prepare many dishes with them.

Pema is the first farmer in the locality to have a greenhouse. Because of her passion for innovation and collaborative spirit, she has been selected by the Agricultural Extension Centre to use the greenhouse for cultivating vegetables. There she has planted tomatoes, cucumber, chilies, climbing beans, salad, amaranth, and other crops. She hopes that the greenhouse will be successful. It will give her more diverse produce throughout the year. She will be able to sell some of the harvest at the market.

The Agricultural Extension Centre provides free technical advice for all agricultural activities. The technician comes to visit the fields every once in a while. She also interacts with the rice researchers and monitors the experiment. Pema is very pleased with her support.

The villagers face several problems, says Pema. "A major problem we have are wild boars. They come from the forest during the night and invade our fields. They dig up the potatoes and empty a field in one 'haul'. We have to stay overnight in the fields to chase them away, but it is not easy. One of my potato fields was invaded some days ago; the boar devoured all the potato seeds. When the maize is ripening, they will return. They also like rice and oats. That is why all our rice fields are fenced."

Another major problem is drought. "This season," Pema observes, "as you can see [she points to some of the affected crops], drought is affecting us in a severe way. For the rice we still have irrigation water, but the reduced inflow has already caused some tensions between households that depend on the same source. The drought could cause for the potatoes to not flower and thus lead to their loss. That would be a serious setback for me. The vegetables, oat, and maize are also suffering. I hope the rains will come soon.”

Rich diversity goes a long way to increase resilience but the changing climate will require new growing options. The National Biodiversity Centre of Bhutan will collaborate with Bioversity International to search for such new options.

Watch this video to learn more about using crop diversity to tackle climate change: Meet Bhutanese farmer Pema