Blog From the Great Green War to Peace in Cacao Production

Some years ago, for the first time (and without much detail) I heard about the conflicts related to the control of the emerald mines in western Boyacá, that took place over several decades. These so-called 'green wars' add one more chapter to the long list of tragic events in our country, Colombia.

In one of our visits to the region of western Boyacá, together with our fellow researchers from the Clima-LoCa project, I was fortunate to hear the stories of former emerald miners of the golden age of production. Today, many survivors of the war are proud cacao farmers, who shared their stories of going from fighting to death with their neighbors, to sharing tips on sustainable cacao farming: ranging from pest management to the cacao varieties work best in their regions.

As part of the socioeconomic component of the project, our goal was to collect information on the context and particularities of the cacao value chain in the region, the conditions of the producers and the characteristics of the region's production systems. To do so, we planned a series of workshops and interviews where producers from different municipalities participated and shared how cacao production has transformed their lives.

Asocacabo Collection Center

The Boyacán economy has had a strong agricultural tradition. However, the opportunities in emerald mining motivated rural communities to abandon their agricultural activities for the more lucrative mining jobs. In one of the workshops held, farmers told us how the emerald mining families, military squads and gangs fought each other for control of the emerald mines. "At that time I couldn't sit by this man next to me like I am today, because we would kill each other" said one of the farmers, referring to another cacao farmer who attended the workshop.

Despair, exhaustion and resignation added to the more than 4,000 deaths from this 'green war', which finally led to the signing of a peace agreement in 1990. However, this was not the end of the conflict. Producers recalled how following these negotiations, rural families began planting illicit crops for their livelihoods; many families turned to the production of coca - the base ingredient of cocaine - in search of a reliable income. The rural people who survived the war had to face another battle that created conflicts between neighbors and friends: the production and commercialization of coca leaf and inputs for the manufacture of cocaine.

One of the producers told us how the conflict and drug trafficking not only took many lives and destroyed communities, but also brought alcoholism, prostitution and great damage to the region, as coca plantations led to the deforestation of important forest areas.

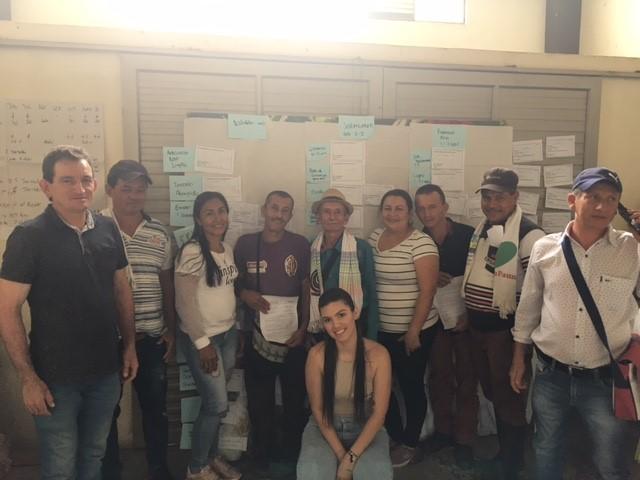

Workshop 1: Producers from San Pablo de Borbur and Muzo

Aproccampa collection center. Workshop 2. Producers from Pauna and Maripi

At this point, the community felt they had only three options: death, the loss of their assets, or the loss of their freedom. Thus, tired of these conditions, in 2004 a group of farmers took the lead and decided to leave coca production and return to agriculture, thus becoming the main organizations of agricultural producers. It was at this time that the transition to cacao began in western Boyacá. Several of the producers we met had decided to invest in cacao as an alternative and legitimate livelihood for their families. Several of them told us that thanks to cacao production, they can now sit down on Sundays in the town center to have a beer, finally with some peace of mind.

Today, these families - and many others who have joined along the way - are part of the 'Fundación Red Colombia Agroperacuaria' ('Colombian Farming Network'), a second-tier organization created for producer associations to support each other to keep their cocoa business afloat. The network currently represents 10 cacao producer organizations from 8 municipalities in the western province.

Workshop 3. Producers from Pauna and Maripi

Although cacao has generated legal incomes and helped restore peace in the region, there are still many needs and challenges that farmers face in their day-to-day work. Changes in the climate and the increase in the cost of labor and inputs have made it harder for families to obtain a decent income, many of whom are still in vulnerable conditions. Furthermore, as many cacao producers are further on in age and young people continue to migrate to cities in search of better opportunities, labor is scarce.

Although rumors of a 'new green war' are emerging, at least war between farming families has ended. However, economic needs and lack of opportunities remain. This is a concern for the community and for some, it brings to mind an idea of returning to the past. However, this worry fades when remembering the hardship experienced. One of the representatives of the first associations said: "Western Boyacá is an example not only of peace, but also of reconversion and abstinence. Every day we fight to maintain the cacao culture and leave behind the culture of war and illegality."

Authors.

Carolay Perea with collaboration of Andrés Charry, research associates, Bioversity-CIAT Alliance ([email protected]), Clima-LoCa project.

Clima-LoCa is a regional project led by the Bioversity Alliance and CIAT, implemented with research partners from Latin America and Europe, and funded by the European Union. The project contributes to the objectives of the 2018 call "Climate Relevant Innovation through Research in Agriculture" of the DeSIRA (Development Smart Innovation through Research in Agriculture) platform.

Disclaimer.

The contents are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Copyright © 2023 Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).