Farmer strategies to adapt to climate change in Colombia

How will rural communities adapt to climate change? Bioversity International and partners are working with communities in Colombia to assess their vulnerability to climate change and develop strategies together.

Read this article in Spanish

How will rural communities adapt to climate change? A common criticism is that governments focus too much on top-down approaches to climate change adaptation, without considering the local needs of rural communities.

As a response, several development agencies have developed participatory planning tools to allow communities to be involved in decision-making processes and share their valuable knowledge and solutions to climate change (such as FAO’s e-learning tool, CARE's IISD’s Cristal Tool, Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis Handbook). These tools help local communities and scientists work together to identify local, daily impacts of climate change and work out feasible solutions.

However, little is known about whether they actually capture all the information relevant to establish climate change adaptation plans. Bioversity International, therefore, has initiated a project in collaboration with the Institute for Development Studies, to test their effectiveness in identifying a community’s vulnerability to climate change.

Last April, Bioversity International staff began working with two rural communities situated in the breathtaking Chicamocha canyon in the Colombian Andes, one of the deepest canyons in the world. The Chicamocha canyon is considered one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change in Colombia, as water shortage and desertification have been increasing in the last decades (IDEAM report 2010).

With the help of Fundación Conserva, a Colombian partner that has been working in the area since 2004, Bioversity International carried out a workshop and survey using a combination of participatory tools, to see whether they could capture the different perspectives of men and women, and of those who are most vulnerable to climate change.

A major challenge was to ensure that farmers attended the workshop, as participation meant foregoing valuable hours of work. The workshops did not offer any direct economic benefit, but previous visits to the area had allowed us to build personal relationships with the local community, and invite them in person to participate.

We also explained that we wanted to help them experiment with adaptation strategies, for instance by providing small amounts of seeds for different crops and varieties. Seeds are an area of strong interest to these communities, mainly because they lack access to even small amounts for home garden crops. As a result, people were very receptive, and welcomed us into their homes, sharing a little of their lives and learning about us, too.

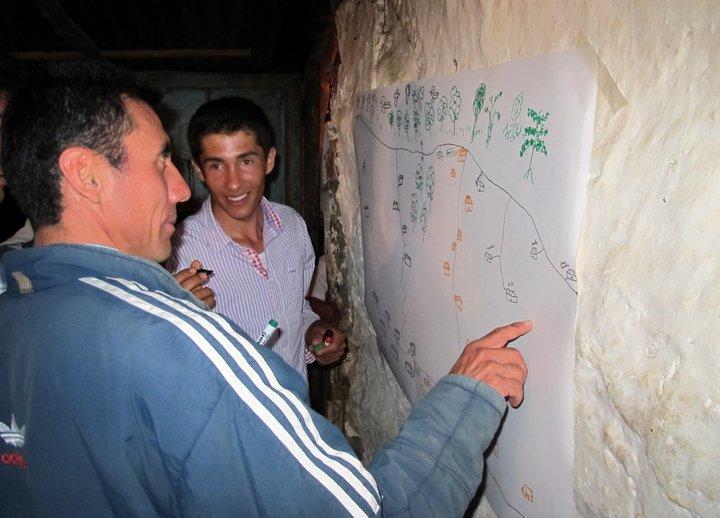

During the workshop, participants were asked to draw a map of their community in order to identify the main physical, natural resource and climate risks that affect their economic well-being. Drawing and painting key aspects of their territory such as houses, main crops, streams and forests, was one of the activities that the participants enjoyed most, and was important for understanding community dynamics, climate hazards, and how to plan for risk reduction.

The workshop allowed us to get a closer look at how climatic events affect local resources. Communities have to cope with long periods of drought that affect their crops and limit crop diversity in the region. Furthermore, certain important crops in the region, such as fique — a fibre-producing plant — are also suffering from other threats.

Farmers producing fique fibre are involved in the growing, spinning, dyeing and making of fique bags, which requires time and effort without necessarily providing a significant income. Historically used for bags to transport products (like jute elsewhere), fique has started being replaced by cheaper materials such as polypropylene. Although those consulted want to replace these crops with others that might provide more income opportunities, abandoning these traditions is not easy. All members of a family are involved in fique fibre production from a very young age, and many do not know alternative ways to earn a living.

One lesson the organizers learned from the workshops is that these participatory tools need to be part of a wider process of involving the community in adaptation interventions with clear benefits.

This could be done in combination with seed introduction (such as Bioversity International’s 'Seeds for Needs' project), or through community innovation funds, such as the Local Innovation Support Funds mechanism developed by Prolinnova, a CCAFS partner organization.

We will continue to work with this community, and carry out more meetings throughout the year to identify local climatic trends, the seasonality of crops in relation to these trends, the level of impact that climate hazards have on livelihoods, and local adaptation strategies. It is important to improve participatory methods for assessing climate change vulnerability to ensure adaptation strategies respond to local needs.

Have a look at this  Flickr photo set about climate change adaptation in the Americas.

Flickr photo set about climate change adaptation in the Americas.