Blog Understanding gender dynamics in the input segment of upgraded value chains for root crops in Vietnam

Harvesting improved cassava varieties in Dong Nai province, Vietnam.

©2015CIAT/GeorginaSmith

Until the early 1980s in South East Asia (SEA), root crops were important for household food security and women played significant roles in these localized, less developed value chains. However, they are now major commercial crops.

Taking cassava and sweet potato value chains in Vietnam as cases, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT and the International Potato Center (CIP) undertook a comparative study (forthcoming) of the gender dynamics in upgraded and localized root value chains with a focus on the input segment.

In 2015, the export value of cassava was about 1.5 billion USD, making cassava the third most important export crop after rice and coffee. In the Mekong Delta region, sweet potato is the third most important crop after rice and maize with increased export-orientation mainly to China. The price of sweet potato is now 6-7 times higher than that of rice. The commercialization of agriculture often raises concerns about gender equality and women’s welfare. These concerns stem from traditional perceptions about women’s and men’s roles in agriculture.

Men are seen as responsible for cash crops, while women are responsible for food crops for home consumption. Women also tend to own and control fewer of productive resources needed to expand or intensify agricultural production (Aguilar et al., 2014; Croppenstedt et al., 2013; Quisumbing, 1996) and are thus more likely to be excluded from the benefits of commercialization.

The research work carried out by the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT and the International Potato Center (CIP), sought to answer the following questions;

- What opportunities to participate and benefit do localized and upgraded export-oriented value chains provide to women and men farmers?

- How far are women involved in decision-making in local and export-oriented value chains?

- What factors influence the level of investment in quality planting materials, fertilizer and crop protection and implications for productivity?

Data and Methods

To simplify the writing, we refer to the more commercial/export-oriented value chains, often characterized by a highly intensive production node, as upgraded value chains, and we refer to the more localized value chains with a less intensive production node as localized value chains.

Value chains differ significantly across territories (provinces and regions) in Vietnam. Upgraded sweet potato value chains are in two main provinces in Vietnam – Vinh Long and Lam Dong. Cassava farmers in all regions have some access to global markets through various complex value chains, but the Southeast region in Vietnam is home to the most commercially oriented value chains and most intensive cassava production system. One province in the Southeast region, Tay Ninh, alone has over 40 cassava processing facilities. Figure 1 identifies the upgraded and localized cassava and sweet potato value chains in Vietnam.

|

|

Upgraded value chains (export oriented, highly commercial, intensive production) |

Localized value chains (less commercial, more localized, low-intensive production) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet potato |

Vinh Long Lam Dong |

Hanoi Ha Tinh Bac Giang |

|

| Cassava |

South East region South Central region |

Central Highlands North Mountains |

The analysis draws on both quantitative and qualitative data sources. The quantitative analyses are based on a household survey with 552 cassava-producing households from four (out of five) major cassava regions and with 377 sweet potato-producing households from five provinces. The qualitative analysis draws on two main cases – one for sweet potato from Ha Tinh and one for cassava from Son La Province in the North Mountainous region.

Main Findings

What opportunities to participate and benefit do localized and upgraded export-oriented value chains provide to women and men farmers?

Intensive, export-oriented value chains are dominated by men. However, in such cases women often have more control and interest in other crops, livestock or off-farm work, suggesting that it is not necessary to see women participate in, benefit and make decisions in all crops equally with men for women to be considered empowered.

More localized sweet potato and cassava value chains with post-harvest technologies provide multiple benefits to women farmers. For example, sweet potato and vines are important gifts to extended families and friends, which in turn functions as a safety net for middle-aged and old women whose income sources are seasonal and limited. This is often neglected in economic analyses.

In addition, sweet potato and cassava are used for livestock feeding, and livestock is an important source of income for women. Cassava and sweet potato are particularly beneficial as livestock feed for farmers with limited land and capital to grow more expensive crops for livestock feed.

Input costs for both sweet potato and cassava in the localized value chains are relatively low as the crops are able to produce decent yields even in marginal lands and with limited inputs. The costs of planting material is low as farmers can often multiply the local varieties or they can purchase the planting material from neighbors. The crops require less weeding and fertilizer reducing not only costs but labor as well.

How far are women involved in decision-making in localized and upgraded value chains?

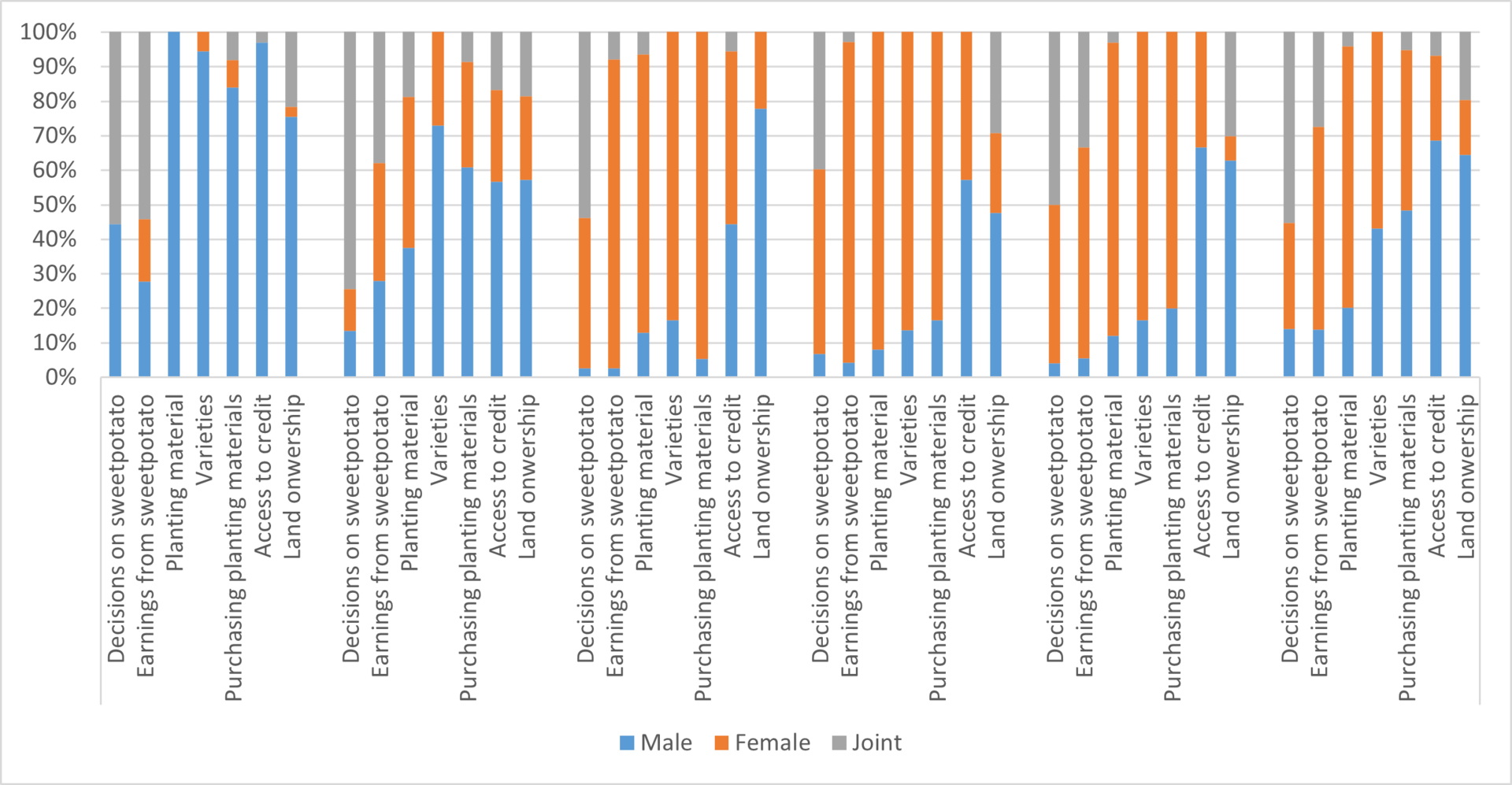

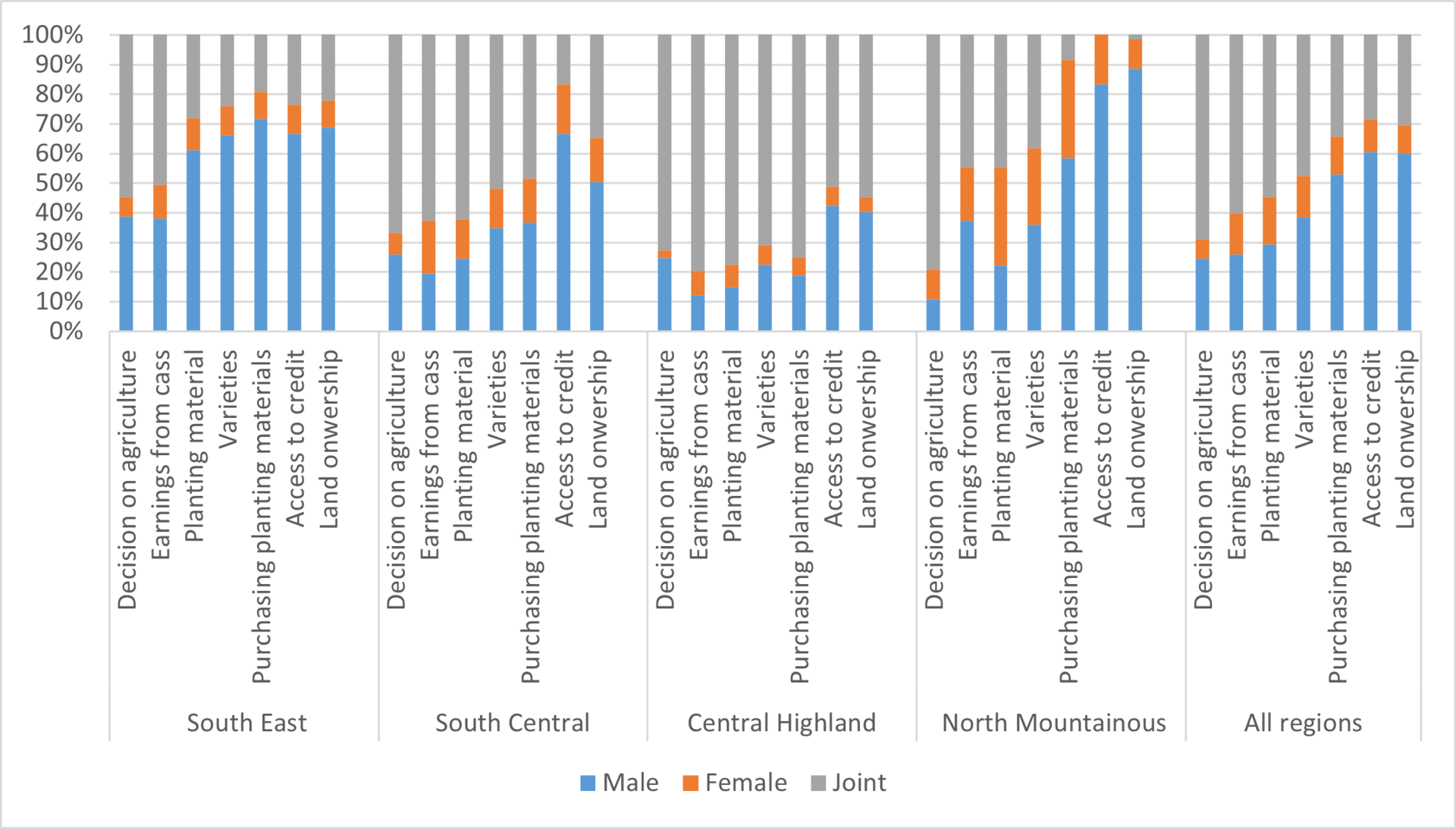

Men are main decision-makers in the upgraded value chains of both crops, particularly around technical decisions such as what varieties to plant and the selection of planting material (Figure 1 and 2). Women are more likely to participate in decisions about the use of earnings. Yet, women are not necessarily excluded from upgraded value chains but joint decision-making is nuanced and not always equal.

Women have more decision-making power in the localized value chains of both sweet potato and cassava. Especially in areas with high male labor migration, there are critical opportunities to support the economic empowerment of women farmers who remain.

Figure 1

Figure 1. Gender patterns of decision-making and asset ownership across sweet potato value chains

Figure 2

Figure 2. Gender patterns of decision-making asset ownership across cassava value chains

What factors influence the level of investment in quality planting materials, fertilizer and crop protection and implications for productivity?

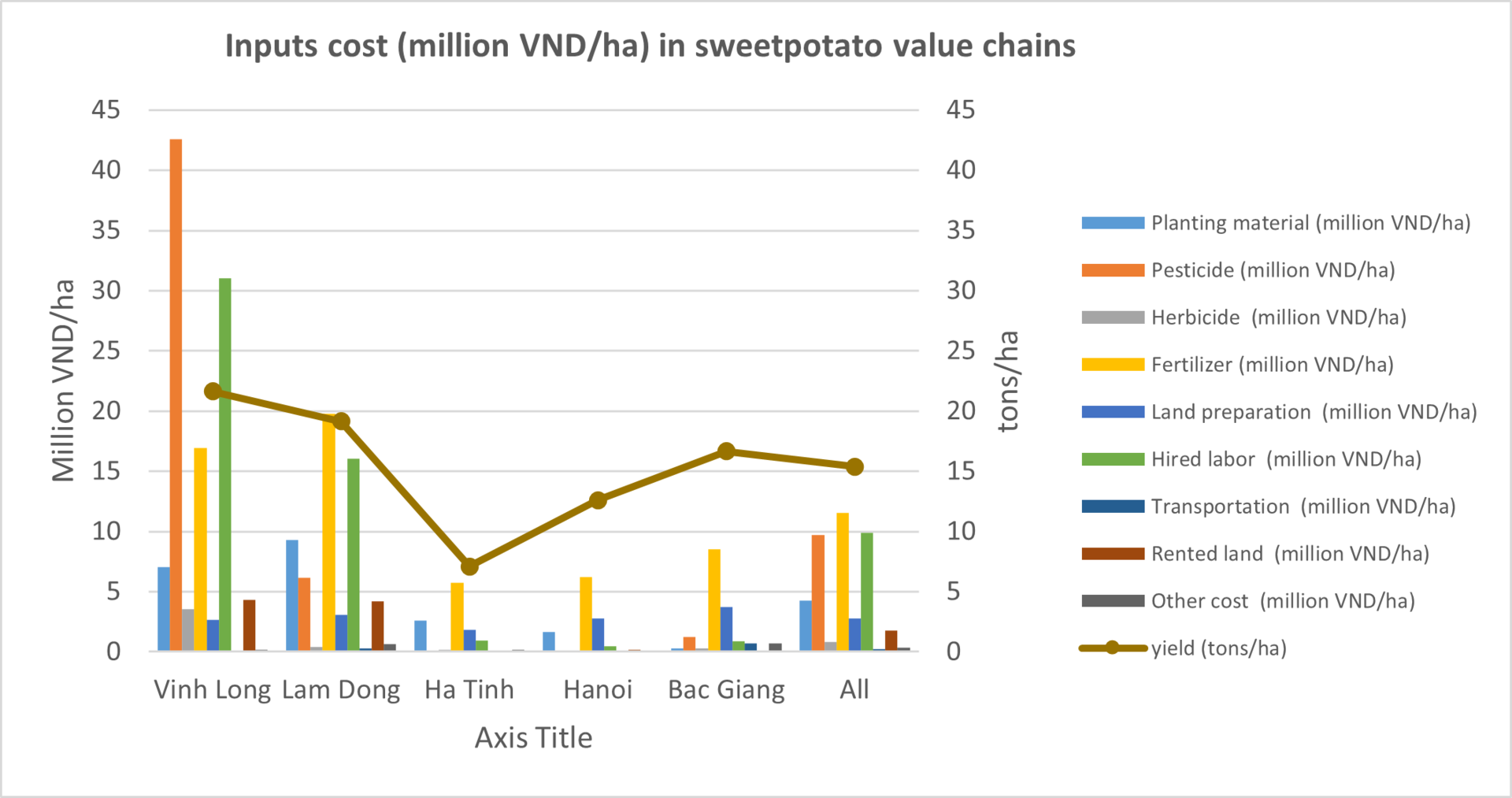

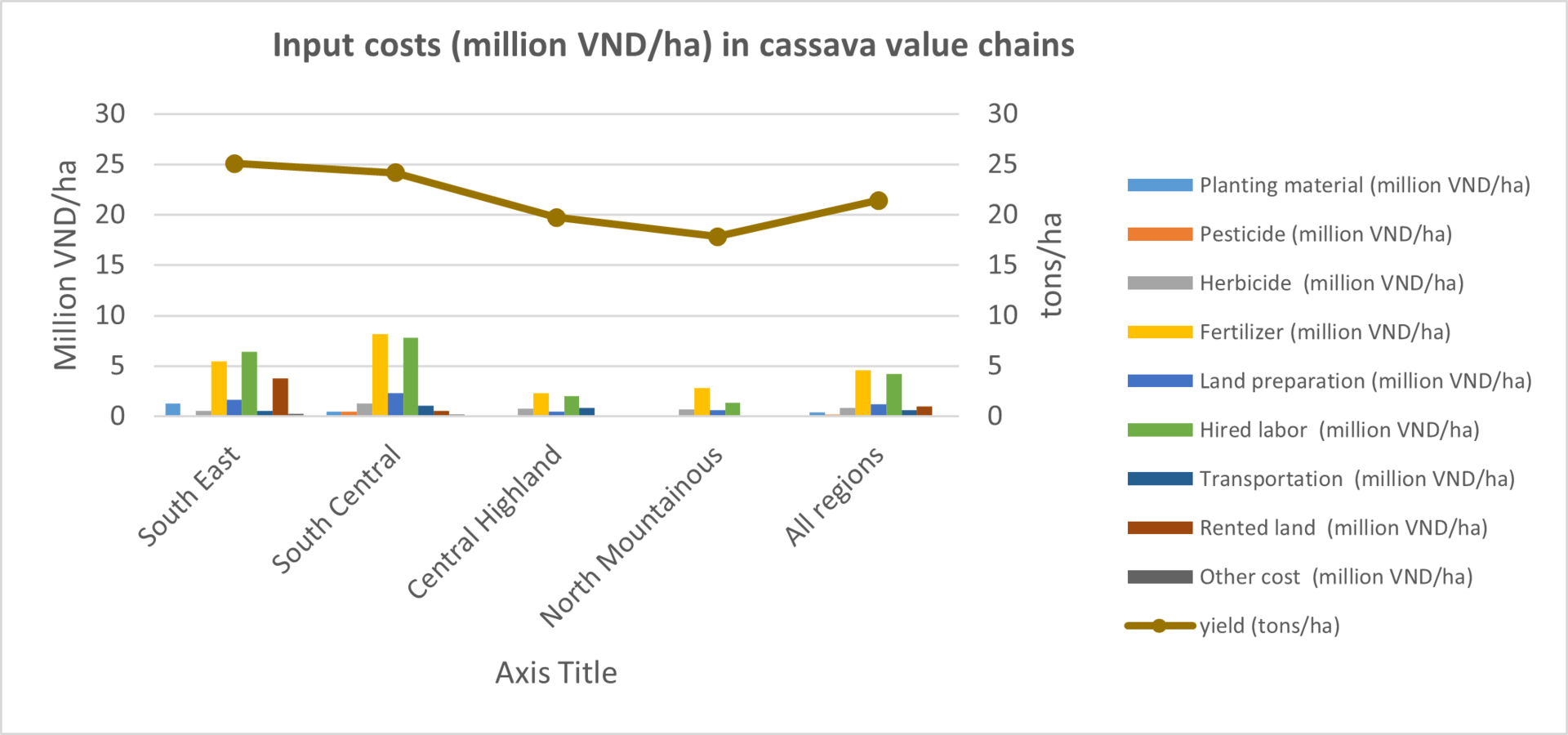

Yields are significantly lower in the more localized value chains compared with the upgraded value chains (Figure 3 and 4). Inputs costs are also significantly lower in the localized value chains.

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Input costs (million VND/ha) and yields (tons/ha) in sweet potato value chains, by provinces. Source: Authors’ estimates.

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Inputs cost (million VND/ha) in cassava value chains, by provinces. Source: Authors’ estimates

The qualitative study, however, suggests that women-led farms may be kept intentionally low-investment as women prefer local varieties which do well with less inputs. Women also have various uses for the cassava and sweet potato (e.g. taste, varieties for animal feeding) and high yield may not be a priority for them unlike in the highly commercial value chains where high yield is the most demanded trait.

Yet, it is also important to recognize that women in Vietnam, regardless of province or region, are less likely to own land and to have access to credit (Figure 1 and 2). They are also less likely to have received any training on either sweet potato or cassava. Interventions in the localized value chains hold great potential to support women’s economic empowerment and welfare, but they are often neglected by agriculture extension services.

The study contributes insights into how the CGIAR addresses gender issues in the processes of increased commercialization and globalization of agri-food systems. Southeast Asia’s on-going shift of root crops from local to commercial value chains can provide many implications for other crops in Africa and other regions where commercialization has only recently started.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to our partners in Vietnam who implemented the two surveys. The sweet potato survey was implemented by the Sub-Institute of Agricultural Engineering and Post-Harvest Technology (SIAEP), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The cassava survey was implemented by the Agriculture Genetics Institute, Ha Noi, Vietnam and the Institute of Agricultural Sciences for Southern Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Phuong Thi Dung Le, Huong Pham, and Duong Ta trained the enumerators and skillfully managed all aspects of the cassava survey data collection and Trang Bui coordinated and managed skillfully the sweet potato survey.

We are grateful to all donors that supported the study. The cassava survey was funded jointly by the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB) and the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM), led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). The sweet potato survey and all qualitative data were funded by PIM. Funding for the analyses and writing of this study was generously provided by PIM, RTB and the Australian Center for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) under the project on Developing Sustainable Solutions for Cassava Disease in Mainland Southeast Asia. We are thankful for the research assistance of Huong Pham and Mary Helen Brighton. The opinions expressed here belong to the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of PIM, RTB, ACIAR, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, CIP, or CGIAR. We declare no conflict of interests.